I. Skepticism Toward the Gospels’ Witness of the Deity of Christ

Bart Ehrman rejects the deity of Christ for two reasons. First, he insists that Jesus did not claim to be God during his lifetime and neither did his disciples. Second, Christian beliefs about Jesus Christ changed over time. The disciples initially regarded Jesus as a man, but after reportedly having experiences of visions of the resurrected Jesus, they concluded that since the exalted Jesus was no longer physically present on earth, God must have taken him to heaven. The Son of Man became the Son of God. At the beginning, there was no belief in the pre-existence of Jesus, but over time the pre-existent Christ was adopted in order to explain the incarnation. Ehrman postulates that the deification of Jesus was due to the influence of pagan mythologies and Jewish angelology.

Ehrman finds no evidence from the gospels that Jesus went about Palestine publicly declaring “I am God.” However, Ehrman fails to consider the historical context which led Jesus to refrain from making such a public declaration. Instead of weighing calmly Jesus’ declaration of deity, the Jews would have reacted violently to Jesus as one guilty of blasphemy. They did try to stone him, after all. It would have been futile for Jesus to try to convince the intransigent Jews who had already made up their minds to reject Jesus’ teaching, no matter what evidence he could offer to back up his claim.

How did Jesus present his claim to be God in such a way that open-minded Jews who were willing to listen will grasp the thrust of his teaching and accept his claim to be God.? His message may be indirect, but it was no less effective in conveying his claim to be God. In his public teaching, Jesus applied the maxim, “Action speaks louder than words,” but privately he explained fully to his disciples his claim to be God. For example, he demonstrated miraculous powers which only God possesses, like calming the storming sea and raising the dead. He arrogated to himself divine prerogatives such as forgiving sin, accepting worship and exercising final judgment. He claimed to be executing divine activities like creation and providence. He even claimed to share God’s eternal existence. [See Is Zakir Naik is too Stubborn to Understand Jesus’ Claim to be God?]

Jesus’ strategy of indirect communication is plainly evident in the gospels. But Ehrman refuses to consider it since he does not accept the gospels as reliable historical records. Ehrman as a critical scholar informed by Enlightenment skeptical rationality insists that the gospels were not written by eyewitnesses. Instead, they were written after Jesus’ apostles had almost all died. They were written in places far from Palestine in a different language, that is, in Greek rather than in Aramaic and were transmitted orally over decades. Ehrman judges the transmission of Jesus’ teaching to be haphazard and unclear, and likens it to “Chinese Whispers” which resulted in embellishments, makeup stories and historical discrepancies.

Ehrman also dismisses the witness of Paul, claiming that even though Paul’s writings predate the gospels, they do not contain explicit historical details about Jesus earthly life and ministry. But why must the historical details of Jesus’ life feature prominently in Paul’s letters? After all, the historical details about Jesus were readily available to the Christian community through the preaching of the apostles. Paul’s personal and pastoral letters served another purpose, which was to address urgent pastoral and missional issues facing the churches which he planted. There was no need for Paul to duplicate the apostles’ authoritative witness to Christ’s life and ministry. Paul was contented to build on the apostles’ witness. He emphasized to the Corinthians that he was passing to them the tradition which he had received. Among the foremost things of this tradition he included Christ’s death, burial, resurrection, and post-resurrection appearances (1 Corinthians 15:3-7). His letters also served as supplements to the apostles’ witness as they conveyed new revealed truths which the resurrected Christ revealed to him after his Damascus experience (Galatians 1:11-17). (Note the careful research by F.F. Bruce, Paul and Jesus (Baker, 1974); Herman Ridderbos, Paul and Jesus (Baker, 1958), David Wenham, Paul: Follower of Jesus or Founder of Christianity? (Eerdmans, 1995) and Seeyoon Kim, The Origin of Paul’s Gospel (Eerdmans, 1981) which confirms the continuity and coherence between the teaching of Paul and Jesus). Paul’s silence about aspects of Jesus’ life should not be taken as evidence of his ignorance about the historical Jesus or disagreements with the Jerusalem apostles’ living testimony. Ehrman is guilty of misplaced expectations.

On the other hand, Paul met the “influential pillar apostles” in Jerusalem, including James, Peter and John (Galatians 2:1-2) to make sure he was not preaching in vain. Surely when Paul met the apostles in Jerusalem, they were not just engaging with Jerusalem high society gossip or discussing the weather? On the contrary, Paul shared with the apostles his Damascus experience which was a “revelation of God’s Son.” The historical records given in the Book of Acts show that Paul and the apostles were in agreement on matters of Christology as the apostles extended the right hand of fellowship to Paul. Significantly, while Paul remained in touch with the apostles (Acts 15: 1-30; 21: 17-20; 2 Peter 3:15-16), there is no evidence that the apostles rejected Paul’s apostolic authority and teaching even though Paul’s letters were widely circulated among the churches.

II. Alleged Influence of Pagan Mythology on Christology

Having rejected the gospels and Paul’s epistles as reliable historical sources of Jesus Christ, Ehrman takes liberty to reconstruct the origins of Christology according to his skeptical presuppositions. He postulates the possible influence of pagan mythology on the development of Christology in the early church. The pagan myths include stories where some gods assumed human forms and engaged in sexual union with maidens which produced divine offsprings, as in the case of Alexander the Great or Hercules. Other pagan mythologies claim that Romulus, the founder of Rome became divine. Ehrman suggests that the idea that Roman emperors could become divine and the requirement of emperor worship could be a source of the Christian deification of Jesus. Ehrman describes his apocalyptic moment,

“As we will see, even though Jews were distinct from the pagan world around them in thinking that only one God was to be worshiped and served, they were not distinct in their conception of the relationship of that realm to the human world we inhabit. Jews also believed that divinities could become human and humans could become divine…And it hit me: the time when Christianity arose, with its exalted claims about Jesus, was the same time when the emperor cult had started to move into full swing, with its exalted claims about the emperor. Christians were calling Jesus God directly on the heels of the Romans calling the emperor God. Could this be a historical accident? How could it be an accident? These were not simply parallel developments. This was a competition. Who was the real god-man? The emperor or Jesus? I realized at that moment that the Christians were not elevating Jesus to a level of divinity in a vacuum. They were doing it under the influence of and in dialogue with the environment in which they lived. As I said, I knew that others had thought this before. But it struck me at that moment like a bolt of lightning.” (HJBG 45, 49)

Ehrman’s suggestion that the early Christians created the idea of a divine Jesus to compete with Caesar worship is psychologically implausible and lacks concrete evidence. Ehrman is effectively disparaging the intelligence of the early Christians – they must be either naïve or half-witted to think that their fabricated crucified savior (albeit a divine savior) could match the invincible might of world-conquering divine Caesars. His suggestion stretches credulity as it requires us to believe that the early Christians were willing to die for a fictional divine savior. It is also puzzling how Ehrman could casually compare the crass sexual details of pagan mythologies with the austere historical narratives of the birth and resurrection Jesus. Ehrman could only suggest some vague parallels between the Bible and the pagan literature. He does not justify why the examples he has given are genuine parallels when Jesus and the pagan heroes are contrasting moral characters. Historical claims are worthy of attention only if they are based on facts and not opinions. Likewise, Ehrman’s suggestion remains an opinion or a conjecture until he can demonstrate concretely how the gospel stories borrowed ideas from pagan mythologies.

Ehrman’s is guilty of literary anachronism in his use of pagan literature. For example, he suggests that the story of Apollonius of Tyana could have influenced early Christian beliefs even though the story of Apollonius was written by Philostratus 200 years after the New Testament. Based on the chronology of the texts in question, it would be more logical to conclude that the New Testament did not borrow from so much as it influenced the story of Apollonius. Ehrman could maintain the theory of pagan influence only by ignoring the fact that the pagans were receptive of ideas from other religions because of their syncretistic outlook, while the Christians were persecuted because of their uncompromising belief in a unique savior and salvation. Ehrman could get away with his unfounded suggestion that Christians were influenced by pagan ideas only because he never fleshes out his simplistic claims.

III. Alleged Influence of Jewish Angelology on Christology

Ehrman’s theory is premised an evolutionary process where Jesus’ disciples transformed the human Jesus (“low Christology”) into the divine Son of God (“high Christology”) after his resurrection. In his words, “it was only after his death that the man Jesus came to be taught of as God on Earth the place to start is an understanding of how other humans came to be considered as divine in the ancient world.” (HJBG 18). However, the historical facts are against Ehrman’s premise. For example, Paul’s letters which date from ca. 50-60 AD, show evidence of a fully developed Christology or “high Christology” which affirms the deity of Christ (Romans 1:3-4; Romans 9:5; Colossians 1:15-20, 2:9; Philippians 2:5-7). This high Christology took place within a period of less than 18 years which is a short space of time of an intellectual process. Martin Hengel concludes, “In essentials more happened in christology within these few years than in the whole subsequent seven hundred years of church history” (Between Jesus and Paul (SCM, 1983), 39-40). Significantly, this Christological development took place in major Jewish-Christian communities in Jerusalem, Caesarea, Damascus, Antioch where both Greek-speaking and Aramaic-speaking believers gathered.

The strong evidence of an early high Christology may have led Ehrman to be careful not to press too strongly the theory of pagan influence on early Christology (except in his debates with superficially informed conservative Christians). Instead, Ehrman focuses more on the thesis that the early Christians were influenced by Jewish angelology. How does Ehrman prosecute his case of the influence of Jewish angelology? He notes that both Judaism and Christianity were not closed to the idea that there exist other divine beings other than God. According to his reading, both Christianity and Old Testament were not so much strict monotheism as “henotheism”, henotheism in ancient times being the view that a tribe may adopt one god for itself without denying the reality of other gods for other tribes. In short, for Ehrman, the henotheistic Jews in the Old Testament did not feel compelled to deny the reality of gods for their tribes and other people.

Ehrman elaborates that ancient Jews in fact believed in a gradation of divine beings, much like the surrounding Greco-Roman culture. The categories of divine beings include 1) divine beings who become human (Angel of the Lord, angels, and “gods” in Psalm 82:1-8), 2) exalted divine figures (Son of Man in Daniel 7:13-14, Wisdom in Proverbs 8, the “Word of the Lord”), 3) semidivine beings begotten from divine beings (Nephilim) and 4) Humans who become divine (Israel’s king in Psalm 2:7; Psalm 110, Psalm 45:6-7 and Moses in later apocryphal texts). (HJBG 62-85)

Jewish angelology flourished in the post-exilic period. Larry Hurtado notes that when the exiled Jews looked around and saw the pagan emperor with his retinue of high officials executing his functions, they decided to explain the sovereignty of their God in analogical language that the pagans could understand. The Jews then described God as presiding over his heavenly court, and his officials or angelic servants discharge his orders and carry out his will. The Jews during the inter-testamental period developed an elaborate hierarchy of angels which included chief angels like Michael and Yahoel. Even Melchizedek supposedly became a heavenly angel. Of great interest is the archangel Metatron in Book of Enoch who receives incomparable divine honors. He may be likened to God’s chief agent, or Vizier. The ancient Jews seem to be to have been rather bold in the descriptive language used for the principal angel that borders toward a deification of this being; nevertheless, it must be stressed that in the devotional life of these ancient Jews this being was apparently not a second object of cultic devotion alongside God.

Hurtado explains,

…ancient Jewish monotheism” was neither “pagan monotheism” (many deities presided over by one high deity, all of them deserving of worship, or one divine notion or being of which all the specific gods are expressive, all of again them worthy of worship), nor was it the “monotheism” of typical modern dictionary definition. The key distinguishing factor, and the most blatant expression of “ancient Jewish monotheism” was not in denial of the existence of other divine beings but in an exclusivity of cultic practice. (OLOG 152)

It is noted that the word “divine” has a spectrum of meanings which includes pagan semi-gods and biblical angels. In some contexts, the word divine is also applied to the one creator God. Ehrman agrees that the early Christians believed Jesus to be God, but for Ehrman the real question is “in whatever senses – plural – since, as we see, different Christians mean different things by it.” (HJBG 84, emphasis in original). Ehrman equivocates and exploits the various senses of “divine” to diminish the status which Christians applied to Jesus.

Ehrman argues that Paul regarded Jesus as the chief angel of the Lord who came in the flesh. He cites Galatians 4:14 where the Galatians welcomed Paul as “as [hōs] an angel of God, as [hōs] Christ Jesus,” that is, the Galatians treated Paul as if he were an angel of God, the same way they regarded Christ Jesus. Ehrman’s equates the two referents “angel of God” and “Christ”, but this is linguistically dubious. For example, Galatians 4:4-6 includes two clauses “God sent forth his Son” with “God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts.” But no interpreter would equate the Son with the Spirit and instead would understand the verses as referring to two divine persons sent from heaven by God. More importantly, the “angel of the Lord” in the Old Testament is never called God’s “son”, and Paul never clearly calls Jesus an angel.

Why does Ehrman resort to such a dubious interpretation? The reason is because equating Jesus Christ with an angel is crucial to Ehrman’s claim that the early Christian were influenced by Jewish angelology. It provides a link for Ehrman to postulate the thesis that belief in the deity of Christ did not originate from Jesus’ self-proclamation but resulted from a long process adaptation of ideas from Jewish angelology found in apocryphal literature. The adaptation climaxes with the high Christology of the Gospel of John.

Ehrman writes,

To summarize our findings to this point: the Angel of the Lord is sometimes portrayed in the Bible as being the Lord God himself, and he sometimes appears on earth in human guise. Still other angels—the members of God’s divine council—are called gods and are made mortals. And yet other angels make their appearances on earth in human form. Still more important, some Jewish texts talk about humans becoming angels at death—or even superior to angels and worthy of worship. The ultimate relevance of these findings for our question about how Jesus came to be considered divine should already begin to become apparent. In one of the important studies of early Christian Christology, New Testament scholar Larry Hurtado states a key thesis: “I propose the view that the principal angel speculation and other types of divine agency thinking . . . provided the earliest Christians with a basic scheme for accommodating the resurrected Christ next to God without having to depart from their monotheistic tradition.” [citing Larry Hurtado, OLOG 82] In other words, if humans could be angels (and angels humans), and if angels could be gods, and if in fact the chief angel could be the Lord himself—then to make Jesus divine, one simply needs to think of him as an angel in human form (HJBG 61).

Michael Kruger convincingly refutes Ehrman’s argument,

Each of Ehrman’s examples of supposed semi-divine figures cannot be addressed here, but he bases his argument primarily on angels, particularly the mysterious “angel of the Lord” phenomenon in the OT. However, the idea that early Christians saw Jesus in the category of an angel runs contrary to numerous other lines of evidence. For one, Jesus is clearly distinguished from the angels (Mark 1:13; Matt. 4:11), given Lordship over the angels (Matt 4:6, 26:53; Luke 4:10; Mark 13:27), and exalted in a place above the angels (Heb. 1:5, 13). In addition, Jesus is accorded both worship (Matt. 28:17; Luke 24:52) and the role of Creator (1 Cor. 8:6; Col 1:16; Phil 2:10-11) – two key marks of God’s unique divine identity within Judaism – whereas angels are never portrayed as creating the world, nor as worthy of worship (Col. 2:18; Rev. 19:10, 22:9). [http://www.reformation21.org/articles/how-jesus-became-god-a-review.php]

Ehrman cites Hurtado to support his theory of influence of Jewish angelology on early Christology, but he is misrepresenting Hurtado. In fact, Hurtado deliberately sets out to correct those who attributed the worship of Jesus to the influence of pagan mythology and Jewish angelology.

[A number of New Testament texts indicate] “a creative and novel appropriation of Jewish “chief agent” tradition [but this tradition]…was not in itself sufficient cause” of the “mutation” in Jewish devotional practice that we see evidenced in NT texts…Rather than trying to account for such a development as the veneration of Jesus by resort to vague suggestions of ideational borrowing from the cafeteria of heroes and demigods of the GrecoRoman world, scholars should pay more attention to this sort of religious experience of the first Christians. It is more likely that the initial and main reason that this particular chief agent (Jesus) came to share in the religious devotion of this particular Jewish group (the earliest Christians) is that they had visions and other experiences that communicated the risen and exalted Christ and that presented him in such unprecedented and superlative divine glory that they felt compelled to respond devotionally as they did.”[OLOG 155, 126]

For Hurtado, the crucial stimulus that led the early Jewish believers to worship of Jesus was not because they identified Jesus as another principal Angel but because they saw the resurrected Jesus as someone elevated next to God and that God specifically requires that Jesus be given cultic reverence, and be included in the worship given to God. As such, the early Christian devotion or worship of Jesus is an expression of faith in the one God.

Michael Kruger identifies a fatal flaw in Ehrman’s hermeneutics:

Ehrman attempts to overcome these clear restrictions on angel worship by flipping them around to his advantage: “We know that some Jews thought that it was right to worship angels in no small part because a number of our surviving texts insist that it not be done. You don’t get laws prohibiting activities that are never performed” (pp. 54-55, emphasis his). Yes, you don’t get laws prohibiting activities that are never performed; but at the same time you can’t use laws prohibiting activities as evidence that those activities actually represent a religion’s views! It would be like using the Ten Commandments (which are filled with prohibitions) to argue that ancient Judaism was a religion that embraced idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, adultery, murder, coveting, and so on. Again, Ehrman is using what is, at best, a condemned and fringe activity (angel worship) as characteristic of first-century Judaism. That simply doesn’t work as a model for how early (Jewish) Christians would have viewed Jesus. [http://www.reformation21.org/articles/how-jesus-became-god-a-review.php]

Finally, Michael Bird delivers the coup de grace to Ehrman’s fallacious postulation of the influence of Jewish angelology.

In sum, therefore, there was in Jewish thought accommodated beliefs and honorific titles given to various agents like chief angels such as Metatron and to exalted humans such as Enoch. However, a sharp line was drawn between the veneration of intermediary figures and the worship of the one God (so Hurtado), and this was based on the fact that such beings were not part of God’s divine identity (so Bauckham). In this case, and contra Ehrman, the continuity between Jewish monotheism and New Testament Christology does not flow from intermediary figures, but from christological monotheism. (HGBJ, 25]

Useful References

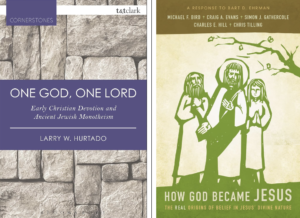

HJBG: Bart Ehrman, How Jesus Became God (HarperCollins, 2014).

HGBJ: Michael Bird, Craig Evans et. al., How God Became Jesus (Zondervan, 2014).

OLOG: Larry Hurtado, One Lord: Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism. 3e (T & T Clark, 2015).

Related Posts

Bart Ehrman’s Historical Revisionism. Part 1/3. Misquoting Scripture

Bart Ehrman’s Historical Revisionism. Part 2/3. Relegating Orthodoxy in Early Christianity

I see Bart Ehrman as an influential “apostate” from the Evangelical faith (2 Pet. 2:1), and a “devil” in the guise of a “learned scholar” being used to further ravage/sabotage the faith of the children of God and disciples of the LORD Jesus. He is ostensibly “much-learned”, but regrettably out of a pervert mind/spirit has employed his “scholarship” for harm/evil rather than good. The wealth accumulated in this regard would one day turn out to be his ruin.

As a direct, succinct and truthful response, we could simply affirm our FULL TRUST in the OT Prophets, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Peter, Paul and the other apostles, and above all the LORD JESUS and the Holy Spirit, who served and spoke in their time and context, and do continue to illuminate, bless and transform our lives today, rather than to follow the many presumptuous “enlightenment” liberal scholars since the 18th century.

We never ever believed that such skeptical/unbelieving/ presumptuous “scholars” know better than the Lord, the Prophets and the Apostles, also the early Church Fathers, however “learned ” they may pretend to be. My personal life-long studies, reflection and practice on the Scriptures result in profound conviction that it is indeed PERFECT WORD OF GOD knit as a seamless divine tapestry meant for the eternal redemption and edification of all humankind, as stated in 2 Tim. 3:13-17.

On the practical educational/apologetic level, I see that ALL the articles that Dr. Kam-Weng has presented in “Krisis and Praxis” over the decades as of the highest standard of intellectual/ scholarly substance and integrity, and are definitely worth collection and publication in paper as well as digital forms for the blessing of the present and the generations to come. May the LORD raise churches/ leaders to make it happen as a most worthy spiritual/intellectual investment for GOD’S glory and furtherance of the Gospel. AMEN.

Hi Kim Sai,

Good to hear from you

Ehrman’s views have been conclusively refuted by well-known scholars, but he just ignores their sound scholarship and keeps repeating his discredited views over the internet. For sure, as a first class communicator, he has successfully garnered hundreds of thousands of followers, but these followers are people who are just looking for any reason not to believe the bible. This includes American nominal and culture Christians in the USA and Muslim apologists looking for ammunitions to attack Christianity. However, Ehrman’s polemics against Christianity (under the guise of objective historical scholarship which is a myth) should have minimal impact on committed Christians, especially those attending churches which are conscientious in teaching the bible.

It would have been natural to expected someone has deconverted (apostatized is the Greek NT word) from his professedly conservative/fundamentalist beliefs would move on to celebrate his new-found freedom. Strangely, he seems obsessed in revisiting his abandoned faith in order to attack it again and again, which seems to confirm the saying about the criminal who revisits the scene of the crime. Is it the case that for all his relentless stabs at Christianity, he is not sure that he has successfully killed his previously held ‘faith’? “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.”

Ehrman’s obsessive attacks against Christianity is quite a sight to behold.