Kairos Podcast 6: Early Trinitarianism from NT to Nicaea. Part 6/6

LINK: The Creedal Imperative and Trinitarian Confession of Christian Faith and Theology

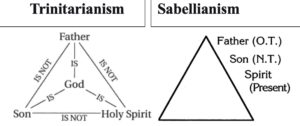

Recapitulation – how the doctrine of Trinity unfolded as the early church countered heresies.

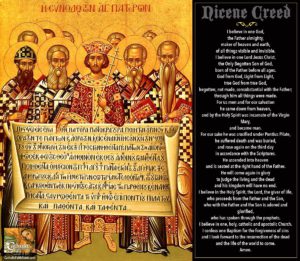

Tertullian defined the Trinity as three persons in one essence, thus highlighting the foundational biblical teaching on the oneness of God and the three distinct yet equal persons of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Council of Nicaea, with Athanasius, applied the term “essence” (ousia) to the person of Christ. Christ is of the same essence (homoousios) with the Father. Yet Christ also exists as a separate person, distinct in his own identity as Christ the Son. In short, biblical-Nicene trinitarianism succinctly insists that Christ is truly God and anyone who teaches otherwise is teaching heresy.

The Creedal Imperative – Biblicism insists that one only needs the bible to formulate Christian belief by relying on rigid proof-texting of selective bible verses at the expense of context and other biblical teachings. In contrast, the historic church affirms that creeds (like the Nicene Creed) are essential as they assist the church in understanding Scripture, provide succinct and normative summary of the foundations of the Christian faith (rule of faith) and protect believers from false doctrines.

You may view the video at

The Creedal Imperative and Trinitarian Confession of Christian Faith and Theology