Part 3: Biblical History & Textual Interpretation

Related Posts:

Part 1/3: Contested Foundations of Archaeology

Part 2/3: Archaeological Evidence – A Reality Check

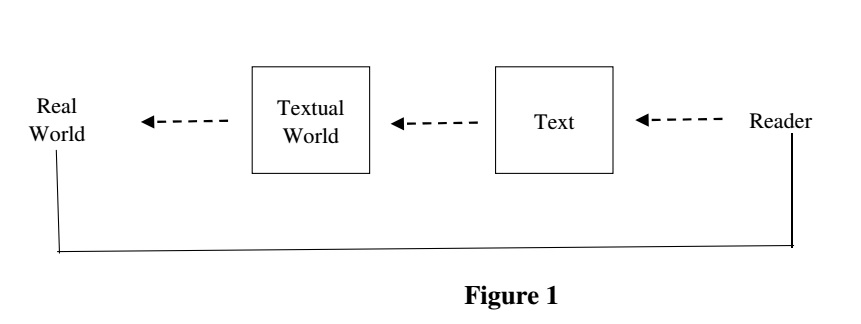

God’s verbal revelation to Israel is inscribed in written texts. The inspired authors of scripture crafted the revealed words into whole texts and into differing literary forms, such as narrative, wisdom literature, poetry and prophetic proclamation. Narratives comprise a significant portion of the inspired texts. These narratives depict a literary constructed world (textual world) which is meaningfully related to the real world. That is to say, the literary constructed world necessarily conforms to the requirements of the real world in order to present a world that bears semblance to empirical reality or life as we experience. This may be represented diagrammatically in figure 1

As a reader reads a historical narrative he is ‘drawn’ into the world of the text, but the text also makes an “ostensive reference” to the real world behind the text which may also be accessed by the reader by other means, e.g. archaeology, relevant historical texts etc. But the two worlds (the world of the text and the background real world) must not be confused or identified.

The narrative text imparts to the reader the perspective of the author who guides the reader through appropriate use of words to form a self-contained and coherent world that constitutes a preinterpreted image of reality. The task of biblical interpretation is to understand the meaning of the text in its narrative form. In the words of John Sailhamer, “Our task is not that of explaining what happened to Israel in Old Testament times. Though worthy of our efforts, archaeology and history must not be confused with the task of exegesis and biblical theology. We must not lose sight of the fact that the authors of Scripture have already made it their task to tell us in their texts what happened to Israel. The task that remains for us as readers is that of explaining and proclaiming what they have written. The goal of a text-oriented approach is not revelation in history in the sense of events (res gestae) that must be rendered meaningful. Rather, the goal is a revelation in history in the sense of the meaning of a history recounted in the text of Scripture. [IOTT, p. 72]

It would be helpful to compare the traditional with the critical understanding of biblical narratives by observing how the reader correlates three spheres: (1) the biblical narratives, (2) the historical events depicted by them (ostensive reference), and (3) the world of the reader.

The Precritical Understanding of Meaning in Narrative

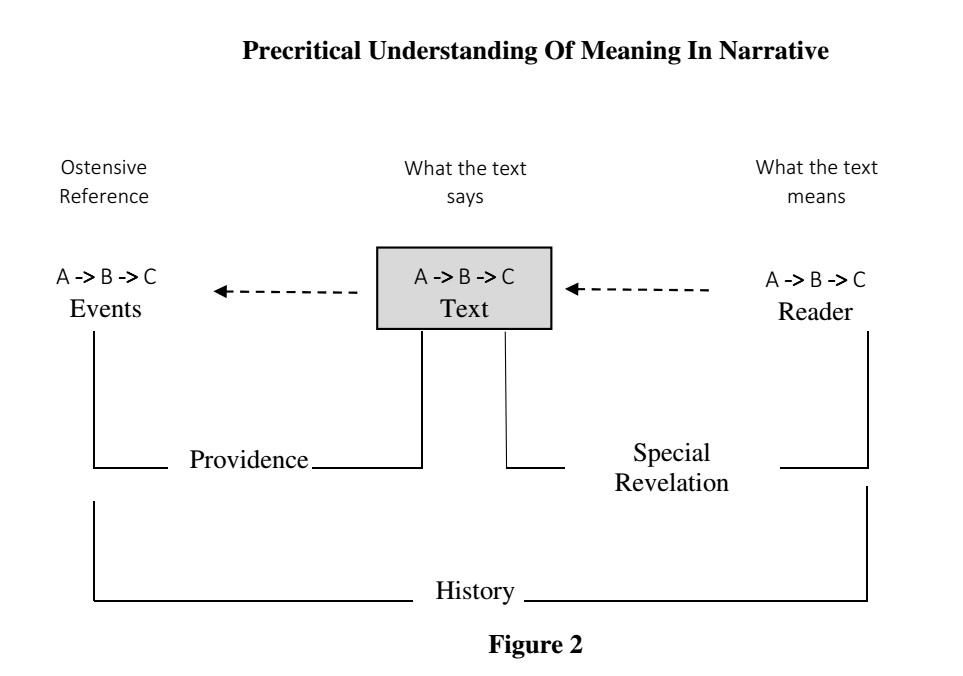

In the precritical view of Scripture (Figure 2), the course of the actual historical events, represented in the chart by A – > B – > C (event A [Israel’s sojourn in Egypt] causes Event B [Bondage under Pharoah] which causes Event C [God’s deliverance through the Red Sea]) is precisely [emphasis added] that which is depicted in the biblical narratives (A – > B – > C) and is understood as such by the reader (A – > B – > C)…According to the precritical view, the event in real life happened just as it is recorded in the biblical narratives (Ge 46 – Ex 15) and was to be understood as such by the precritical reader. [IOTT p. 75]

The Critical View of Biblical History

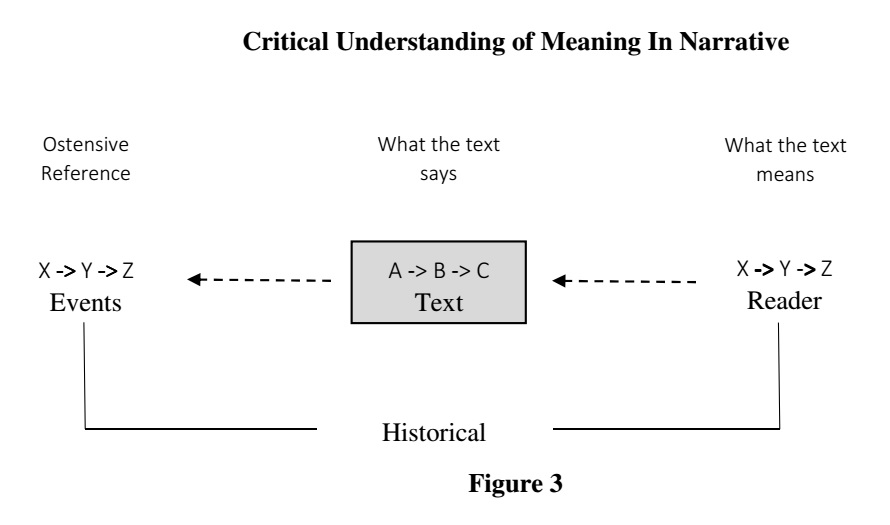

Figure 3 shows that there are fundamental differences between the critical and the precritical view of biblical narrative. In the critical view, the actual event in history (X – > Y – > Z) are not identical with the depiction of these events in the biblical narrative (A – > B – > C). As an example, the biblical text recounting the story of the Israelites’ move into Egypt (A), their enslavement by Pharaoh (B) and their deliverance from Egypt under Moses (C). The actual course of events may turn out to be different. According to many critical scholars, there were no Israelites before the Exodus (X). Only a small band of slaves escaped from of Egypt after crossing a sandbar at low tide and fleeing into the desert (Z). The two accounts not only contradict one another, but critical scholars argue that the meaning of the text should be defined by its ostensive reference or the “real” events at the background (X – > Y – > Z). The narrative meaning (A – > B – > C) is replaced by the meaning of the actual events (X – > Y – > Z) as if that was really what the biblical narratives were about.”

The reason for this change of focus is because of the influence of Deism and the rejection of miracles in contemporary historical criticism. If a biblical narrative contains reports of miracles it must be rejected, and critics should reconstruct the “real’ events behind the text. Hence, for the critical historian, the meaning of the text is based on the ‘real’, critical reconstructed world behind the text (X, Y, Z) rather than the narrated events in the text (A, B, C).

The Conservative Historical View of Biblical History

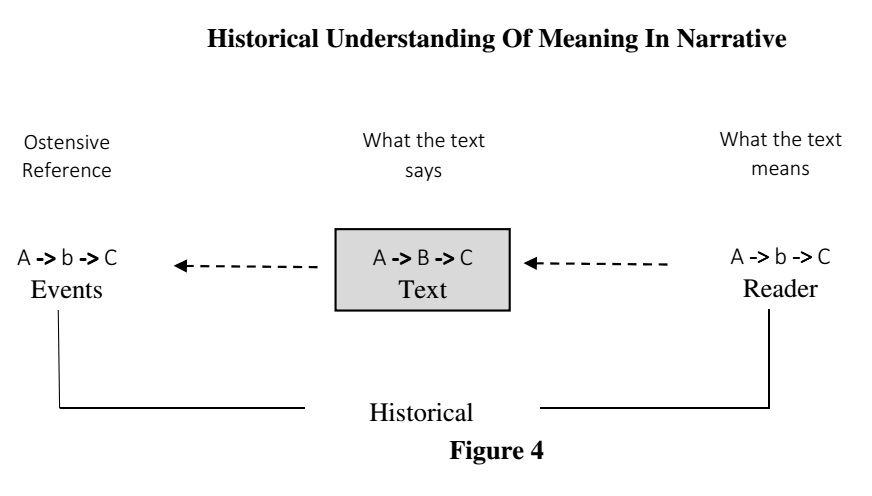

Some conservatives recognize the need to engage with critical reconstruction of the events behind the texts while maintaining that the events narrated in the text is largely accurate. A compromise is struck by making a slight adjustment to the world behind the text. This is signified by “b” in figure 4.

Though the text is by and large historically accurate, the actual event (b) referred to in the biblical text (B) is adjusted to what reasonable (uncritical) historic method suggests “actually happened.” Since the text is read in terms of its ostensive reference, the reader’s understanding of the meaning of the text is in fact that which he or she knows to have “actually happened” (b) (IOTT, pp. 79-80)

Whether this compromise is acceptable to the community of faith, or whether the compromise is a slippery slide towards critical scholarship is a matter of debate.

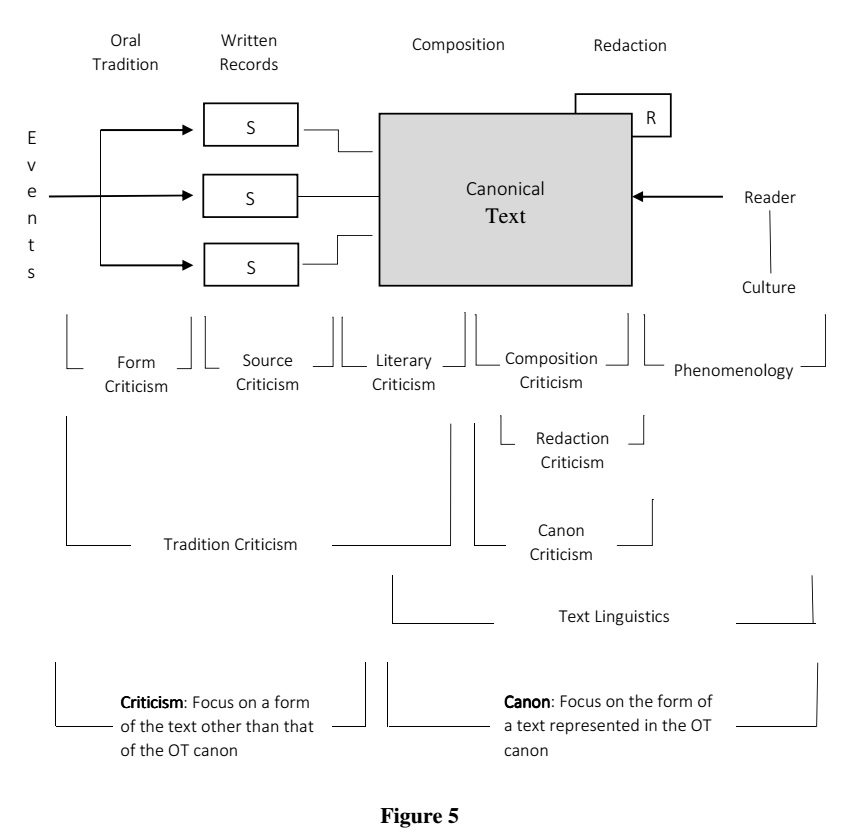

Critical Canonical Stages Biblical Narrative

We shall only note in passing the dynamics for a full canonical reading of the text which would requires applying a range of critical tools onto the text: Form criticism on oral tradition, Source criticism on written records, literary criticism on the composition of the text, composition criticism on the redaction process of the text and finally a phenomenology of the reader and reading in a cultural context. These various processes of criticism however must be seen as only preparatory, the ‘antechamber’ to the ‘chamber’ of an actual reading of the final text on its own terms. [IOTT p. 102]

Text-Oriented Interpretation of the Old Testament

The validity of historical criticism understood as a task to recover and comprehend the ‘real’ events ostensibly referred to by the biblical narratives using whatever tools of modern archaeology and literary criticism should be acknowledged. The priority given to the world of the text should not be taken as a claim championed by the minimalists that there was no real background history to the text as they then take license to mount a deconstructive literary reading of the biblical text. William Dever gives a proper assessment of the biblical historical narrative, “Despite the fact that literature is not a direct reflection of reality, it is deliberately “intentional.” It is (a) written for a specific audience, however limited; and (b) intended to communicate a certain vision of reality, primarily the “inner reality” of the author’s experience, but inevitably reflecting at least something of the external (or “real”) world. It both reflects and refracts a vision of reality, perhaps transcending history, but not thereby obliterating it.” [Dever WBWK 19]

Recognition of the ostensive world ‘behind’ the text must not set aside or erase awareness that alongside the ostensibly referred (real) world, there is also the ‘world of the biblical text’ with its own coherence and validity. The fundamental question is to determine whether to locate divine revelation in the text of Scripture or in the events to which the Scriptures refer. Our contention is that only a text-oriented approach gives due recognition to revelation in Scripture. Several consequences flow from this affirmation [See Sailhamer IOTT, pp. 83-85 for a complete discussion]

1. The words of Scripture and the meaning of the biblical author are the first and primary goal. Our methodology and approach to OT theology should reflect this primary goal. Divine revelation in God’s mighty acts in history is acknowledged, but our only access to divine revelation now is through the interpretation of the inspired writers in the text of Scripture.

2. The locus of revelation is the final form of the written text, regardless of whatever layers of prehistory or sources that historical criticism may have identified.

3. The text of Scripture must be kept distinct from its socio-religious context. Knowledge of the socio-historical-religious background sometimes provides insights for understanding the text, but it is not part of the inspired meaning of the text. The text conveys whatever meaning the author intends.

4. Understanding the Authorial intention of Scripture (that is the message of revelation) requires reading the biblical text on its own terms. More accurately, understanding demands the reader enters the world of the text. The biblical narratives does more than present a historically accurate representation of the external world; it re-presents the world of the text to the reader as the real world and is imperialistic in its demands that the reader be ‘absorbed’ into this world. This capacity is described by Eric Auerbach as “mimesis”. In Sailhamer’s words, “The biblical narratives are not content to leave the task of representing history to allegedly neutral or independent sources. The only history, the only world that matters, is that which is depicted in their own stories. The reader is invited to become a part of that world and to make its history the framework for his or her personal life. The reader of the Bible is called upon to submit to the reality represented in Scripture and to worship its Creator.” (IOTT p. 216)

** The above thoughts are gratefully plagiarized from John Salihamer’s book, Introduction to Old Testament Theology [IOTT] which is unfortunately neglected by critics today.

Concluding Thoughts

It may be admitted that the resurgence of text-oriented interpretation can be a reaction to the uncertainties generated by unresolved controversies in historical criticism. As faith cannot simply rests on the shifting sands of historical criticism, text-oriented interpretation ventures into its own inquiry into the world of the text, based on the presupposition that divine revelation and the self-witness of scripture, and assured that the world of the biblical text has its own coherence and epistemological sufficiency.

There is a danger of subjectivism for text-oriented interpretation when the self-sufficiency of the reader’s reading of the text is exaggerated and ends up as a self-referring and absolute reality. One wonders if a text-oriented interpretation that refuses to take into consideration the external, concrete world is left bereft of independent evidence that could either collaborate a right reading of the text or correct a wrong reading of the text. It seems that interpreters like Sailhamer have reacted too strongly to critical historians who demand that the world of the biblical text be forced into the procrustean bed of the background world recovered by modern criticism which requires discarding of the supernatural elements (such as diving revelation, prophecy and miracles) and threatens to emaciate or desiccate Christian faith.

Perhaps there could be a broader interpretation that gives priority to the text and yet is open to incorporate the results of believing historical criticism that admits the reality of divine intervention in history. If text-oriented interpretation already acknowledges that the world of the text bears some semblance (but not identity) with the ostensive background world, then more consideration could be given to the background world reconstructed by historical criticism. After all, if all truth is God’s truth, believing criticism is optimistic about integrating the world of the biblical text with the background world of recovered by historical criticism, even though any integration is tentative and subject to further refinement.

We recommend the guarded optimism of Iain Provan and his colleagues in keeping a balanced relationship between archaeology artifacts and non-biblical texts with the biblical texts, “We do not take these texts more seriously than the biblical texts…Neither do we take them less seriously than the biblical texts, however. For one thing, they provide the context within which we can develop precisely the literary competence mentioned above, as we form judgments about matters of literary convention in the ancient world. For another, the nonbiblical texts provide helpful information about the peoples with whom ancient Israel came into contact, and sometimes about their specific interactions with Israelites. They do not do this in a way that is free of art and ideology on the part of their authors, and so they cannot be regarded as providing more solid information than our biblical texts about ancient Israel. Yet hearing their testimony is appropriate and important, as is exploring how it converges or fails to do so with Israel’s, in forming our view of the shape of the past” [Iain Provan et.al., A Biblical History of Israel (WJK 2003), p. 100.]

Finally, Geerhardus Vos, the father of biblical theology has pioneered an approach to biblical interpretation that holds in balance the tension between the world of the text and the world behind the text, even as he emphasizes that priority be given to the text. For Vos, God has acted in history to reveal himself and to bring about the salvation of mankind. Biblical theology studies special revelation as it is revealed historically so that it exhibits the “organic growth or development of the truths of Special Revelation from the primitive preredemptive Special Revelation given in Eden to the close of the New Testament canon.” As recorded divine revelation is guaranteed by the authority of God, there is no difference between the biblical records and the real events they recount [note that I am siding with Vos over Sailhamer on this issue].

As such, there can be no separation of the textual world from the extra-textual realities which the text points to as the reader responds to the Christ revealed in the text (divine revelation) by entrusting his life to the incarnate Jesus Christ of history who reconciles us to God through his death and resurrection (divine redemption). The two-fold aspects of divine revelation and redemption lead to two related tasks: 1) the task of studying the history of Israel is to trace God’s work of redemption while 2) the task of biblical theology is to trace God’s work of revelation. In Vos’ words, “…in reclaiming the world from its state of sin God has to act along two lines of procedure, or corresponding to the two spheres in which the destructive influence of sin asserts itself. These two spheres are the sphere of being and knowing. To set the world right in the former the procedure of redemptive is employed, to set it right in the sphere of knowing the procedure of revelation is used. The one yield Biblical History, the other Biblical Theology.” [Geerdhardus Vos, Biblical Theology, p. 24.]

The nature and goal of biblical theology will be elaborated in some future posts.

Added on 25/04/2016. Thankfully, no need now for me to write. Get a better resource free from Crossway which is giving a free e-copy of James Hamilton, What is Biblical Theology (Crossway 2013) – LINK

———————————

APPENDIX

Confessional Scholarship and the Role of Comparative Studies

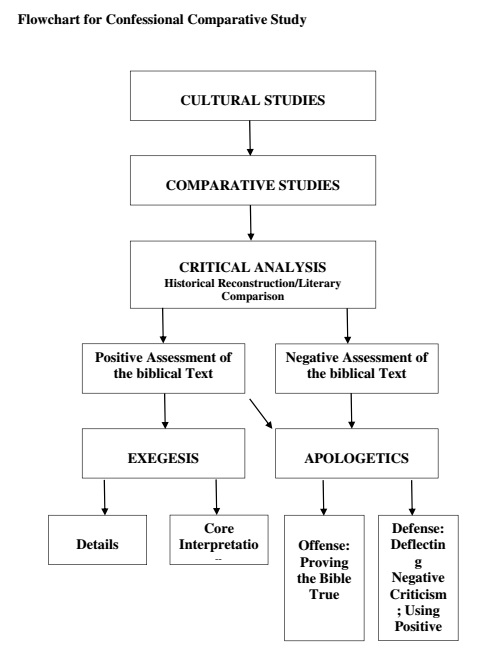

Given below is a (almost verbatim) summary John Walton’s approach to comparative studies of the Bible and the Ancient Near-Eastern Context, followed by a self-explanatory flowchart.

The chart below shows how comparative studies can be used in the pursuit of historical or literary analysis, and from there to engage in either apologetics or in exegesis. With all these alternatives before us, it would be a mistake to think that one of the major questions of comparative studies was to determine who borrowed what from whom, an approach that is all too common.

However, we must be mindful of four potential detractors when we engage in comparative investigations:

1. The need to defend the uniqueness of the Hebrew Bible as Scripture. Whatever linguistic, cultural, or literary features might indicate its ancient Near Eastern character, we accept by faith and by reason that the Bible’s divine source distinguishes it from all other literature.

2. The need to prove distinctiveness. Every culture is distinctive and comparative studies must constantly keep this in mind.

3. The need to contend for literary borrowing. Literary trails are complex. Diachronic assessments are rarely possible and are not necessary for synchronic study.

4. Anxiety that ancient Near Eastern connections will undermine or degrade the Old Testament text. The understanding of the text can be advanced by any information that can help us penetrate the way an ancient author thought.

The uniqueness of Israel within the ancient Near Eastern cultural context is related to the uniqueness of her God, Yahweh, and the uniqueness of Yahweh underlies the uniqueness of the literature that is presented as His self-disclosure. Once we are comfortable with that uniqueness and acquainted with its ripple effects, we will experience the freedom to explore and appreciate the full range of cross-fertilization that exists at other level between the culture and literature of Israel and the cultures and literature of the ancient Near East. If the major observable distinctions are connected to the conception of deity and its related issues, then we should conclude that revelation is at the root of those differences. Conversely, where we do not see revelation as transforming some aspect, we should expect a high level of continuity. We might summarize these thoughts by suggesting that discontinuity with the ancient Near East will emerge more prominently when we study the Old Testament as Scripture. Continuity will emerge more prominently when we study the Old Testament as ancient Near Eastern literature. It is important to note, however, that even when the discontinuity is significant, that discontinuity is communicated within the framework of an ancient Near Eastern worldview, which necessitates comparative study to clarify the nature of the discontinuity. [emphasis added, c.f. postscript]

Source: Israel: Ancient Kingdom or Late Invention, ed. Daniel Block. B & H, 2008. pp. 301-303.

Postscript: John Walton’s set of proposals is most instructive, but there are problems with his last (italicized) sentence. It explains why Walton argues recently in The Lost World of Genesis One (IVP, 2009) that the Genesis narrative not only shares commonality with its neighboring cultures, but that the Genesis creation account should be understood in ‘functional’ rather than ‘material’ categories of origins. Walton thinks his proposal will sidestep the apparent conflict between the Genesis account and modern evolutionary science. However, Walton’s proposal is questionable as it suggests that God revelation is accommodated to the erroneous views of its neighboring cultures. It also renders the Genesis account irrelevant to the scientific quests for the origins of creation. Perhaps Walton should be more consistent with his own view of the uniqueness of Israel and her God.

Two further cautions should be noted.

First, critics assume that the Bible has been significantly influenced by its neighboring religious cultures because the faith of Israel was transmitted primarily through oral tradition during its early history. The texts were eventually inscribed and collated centuries later, during the Babylonian exile. Since oral tradition is by nature fluid and subject to alterations, critics conclude that Israel must have adopted and adapted religious-cultural elements from the surrounding cultures based on what critics identify as ‘ruptures’, ‘discontinuities’ and editorial intervention in the biblical text.

However, Exodus 17:14 implies written religious texts existed among the Israelites from the time of Moses. Israel would have been introduced to writing as it was situated at the crossroads of intersecting cultures with centuries of writing like Egypt, Mesopotamia and Assyria. Recent evidence points to more widespread literacy among Jews than earlier acknowledged. See also Meredith Kline, The Structure of Biblical Authority (Eerdmans 1975) for evidence of historical continuity in Israel’s prophetic traditions.

Second, it is legitimate for the reader to try understand the Bible through the lenses of its neighboring religious cultures which may help to bridge the cultural gap and historical distance between the contemporary reader and the original context. However, we should not forget that the Bible has its own literary and religious integrity. It is no less crucial for the reader to look at the neighboring religious cultures through the lenses of the Bible. Specifically, the stark contrast between the Bible and nonbiblical texts would suggests that Bible itself represents a monotheistic critique of neighboring mythological polytheism. In this regard, to conclude congruence of thought based on similarities of forms would be to misunderstand the Bible.

Recommended Texts by Believing Historians

Bill Arnold & Richard Hess. Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources. Baker 2014.

Richard Hess. Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey. Baker 2007.

Iain Provan, Philips Long & Tremper Longman. A Biblical History of Israel. Westminster 2003.

Related Posts:

Part 1/3: Contested Foundations of Archaeology