Death, Resurrection and Life Everlasting – DRLE Pt.1

Death, Resurrection and Life Everlasting – DRLE Pt.1

A. Contemporary Criticism Against Biblical Dualistic Anthropology

Our understanding of death and afterlife depends on what Scripture says about the nature of man. However, the OT presents no systematic discussion of the nature of man, any more than it does of the nature of the triune God. Nevertheless, the Bible often refers to human nature as dualistic, that is, human nature is a combination of two distinct and separable entities, the material body and the immaterial soul which survives death.

However, the contemporary intellectual climate is inimical toward the traditional Christian teaching of dualism. The various objections raised against dualism include the following: 1) The theory of evolutionary psychology and scientific naturalism undermines belief in the human soul. 2) New research in neuroscience and behavioristic psychology claims to have identified direct causal relation (although this at best could be correlation) between brain functions and states of consciousness. This has rendered irrelevant the idea of the faculties of the soul & a fortriori the idea of the soul.

Under the influence of prominent liberal scholars like Adolf Harnack in the early 20th century, the movement to decouple biblical theology from the alleged influence of Greek or Platonic philosophical influences gained momentum. Dualism is supposed to have resulted in harmful consequences because of its binary categories and false dichotomies – social gospel vs individualistic gospel, man vs environment, male vs female categories, the root of patriarchal dominance and sexism etc. Scholars began to argue that biblical anthropology is essentially monistic or holistic, and does not recognize the duality of body and soul. They even doubt that the terms “soul/spirit” refer to an immaterial entity which survive death.

However, it should be noted that the biblical terminologies of body, soul and spirit have no similarities with Platonic or Cartesian categories. Indeed, biblical anthropological categories are used with a range of meanings. For example, bāśār (flesh) can refer to the muscle tissue or to the entire human body. “But never is bāśār used in a way which would imply a metaphysical distinction between living physical matter and nonphysical substantial spirit”. [Cooper, pp. 41] Likewise, nepeš and rûaḥ (“soul” and “spirit” respectively) do not just refer to a part of a person; they can refer to the whole self. The distinctive usage of biblical anthropological terms should alert us to the need to examine Scripture on its own terms in order to resolve the controversy between holism and dualism. This post shall examine closely how the terms which describe the constituent elements of man are used in the OT (we shall examine the NT anthropological terms in a later post).

B. Man’s Constituent Elements

Bāsār, Flesh

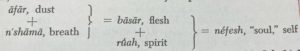

The duality of man is revealed in the creation account of man in Genesis. Adam was created from dust (Gen. 3:19), but an additional spiritual element was added on him (Gen. 1:26). Man is a creature of flesh, bāsār. The Hebrew word bāsār, “flesh,” is composed of āfār, “dust,” and נְשָׁמָה nešâmâ “breath” (Gen. 2:7). Nəšāmâ, carries the idea of life-breath and so comes to mean “life” (1 Kings 17:17; Job 27:3; Isa. 2:22).

Like many Semitic words, “flesh” has a range of meaning in the OT. It is what man has in common with other living beings, that is, his muscle tissue which is distinguished from bones: My bones cleave to my flesh” (Psa. 102.5). More frequently flesh denotes the entire body: 1 Kings 21.27; 2 Kings 6.30; Num. 8.7; Job 4.15; Prov. 4.22, and it can be the seat of spiritual faculties as well as of genuinely fleshly desires, both of which are bound up with the body.

Note that flesh does not connote the principle of sin or the man’s unregenerate nature. It connotes a nature which is frail and transient: “all flesh is grass” (Isa. 40:6; Psa. 78:39). Its weakness makes it vulnerable to being exploited by sin. Edmond Jacob writes, “flesh is a very favourable ground for sin, as is shown in the early pages of Genesis. In the Old Testament flesh is always what distinguishes man qualitatively from God, not in the sense of a matter-spirit dualism, but of a contrast between strength and weakness (Gen. 6.3; Isa. 31.3; 40.6; 49.26; Jer. 12.12; 17.5; 25.31; 32.27; 45.5; Ezek. 21.4; Psa. 56.4; 65.2; 78.39; 145.21; 2 Chron. 32.8).” [Jacob, p. 158] However, “flesh” is open to God’s positive influence so that a heart of stone could be changed into a heart of flesh, something which is soft and yielded to God (Ezek. 36:26).

Nepeš, Soul

“Then the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature, נֶפֶשׁ חַיַּה nepeš ḥayyâ” (Gen. 2:7). nepeš ḥayyâ is applied to both men and animals (Gen. 1:20, 24, 30; 2:19), but man alone is special as he receives the vital breath directly from Yahweh. However, nepeš is not given to man as a spiritual soul deposited in a material body; nepeš is at once physical and spiritual.

Sometimes, nepeš is used anatomically as in “throat” or “neck”, e.g., “his nephesh was put into irons,” (Psa. 105:18). Following the synecdoche usage of language where a part of something is used to represent the whole, nepeš has bodily desire or appetite for food. One can speak of the thirsty soul (Psa. 107:9) or a soul thirsting after God (Psa. 42:1). Nepeš is frequently used in connection with the emotional states of joy and bliss (Psa. 86:4; Job 27:2). Since personal existence by its very nature involves drives, appetites, desires, will, nepeš denotes the “life” of an individual (Lam. 1:16). The nepeš, “soul,” is the entire man and nepeš may therefore often be translated simply as “self,” a “person” (Gen. 12:5; 17:14). It can simply mean the vital principle or life-force of the person. These texts regard man not dualistically, but as a whole. As such, nepeš ḥayyâ is best translated as “living creature” or “living being.”

Barton Payne summarizes accordingly:

The basic meaning of néfesh appears to be “breath” or “throat” (Isa. 5:14; Hab. 2:5). So in passages such as Job 11:20; 31:39 to lose one’s life is literally to “breathe out néfesh, soul.” Then, since the breathing being is alive, néfesh comes to mean life (cf. Jer. 38:16) or living creatures (Gen. 9:12). This significance is demonstrated in Deuteronomy 12:23 where blood meaning “life blood,” has a similar connotation: “The blood is the néfesh [life], and you shall not eat the néfesh with the blood.” Or again, perhaps from the “throat” etymology, néfesh may mean “appetite, desire” (Eccl. 6:9; cf. v. 7). In any event, néfesh comes eventually to equal what thinks and feels, namely, the whole man (Gen. 34:3; Ps. 42:2), an individual “soul.” Though usually treated as immortal, the soul may thus be said to “die” (Judg. 16:30; Num. 23:10). As Schultz puts it:

“Souls” just means men, persons. Hence since a dead person is still “somebody,” it is strictly correct to call him “a soul.” Thus a man can say, “let my soul die,” “my soul lives”; while, on the other hand, death is the departure of the soul, and a person lives by his souls. [Payne, pp. 224-225]

It is before Yahweh that man dialogues with his nepeš (Psa. 103:1, 42:5, 11; 43:5) and where his needy life and desires turn to joyful praise. Hans Walter Wolff concludes, “before Yahweh, man in the Old Testament does not only recognize himself as nepeš in his neediness; he also leads his self on to hope and to praise.” [Wolff, p. 25]

Rûaḥ, Spirit

Rûaḥ can refer to wind or human breath. Frequently, it refers to the spirit of God. In Gen. 2:7, rûaḥ is used as a parallel term with nəšāmâ, “the breath of life”. Job 34:14 says that “if he [God]…gather to himself his spirit (ruach) and his breath (nəšāmâ), all flesh would perish together, and man would return to dust.”Rûaḥ is vital power which animates all living creatures. Rûaḥ points to man as he is empowered.

Man in his dual composition possesses active power or spirit (rûaḥ) which comes from God. The noun rûaḥ, further, depicts disposition of mind or the entire consciousness of man: “With my spirit within me I will seek you earnestly” (Isa. 26:9); a wise man “rules his spirit” (Prov. 16:32; cf. Dan. 5:20). Flesh (bāsār) and spirit combine to form the “self.” At death the body returns to dust, but the immortal spirit returns to God who gave it (Gen. 3:19; Eccl. 12:7).

There is an overlap between rûaḥ and nepeš (soul) in their semantic range of meaning. (Job 7:11; Isa. 26:9; cf. Exod. 6:9 with Num. 21:4). Gleason Archer highlights the overlap and distinction between rûaḥ and nepeš:

Rûaḥ is the principle of man’s rational and immortal life, and possesses reason, will, and conscience. It imparts the divine image to man, and constitutes the animating dynamic which results in man’s nepeš as the subject of personal life. The distinctive personality of the individual inheres in his nepeš, the seat of his emotions and desires. rûaḥ is life-power, having the ground of its vitality in itself; the nepeš has a more subjective and conditioned life. The NT seems to make a clear and substantive distinction between pneuma (rûaḥ) and psychē (nepeš). [TWOT, p. 837]

Walter Eichordt fine-tunes the distinction between rûaḥ and nepeš. “If nepeš is the individual life in association with a body, rûaḥ is the life force present everywhere and existing independently over against the single individual. [Eichrodt, OTT vol.2 p. 136]

Barton Payne gives a helpful chart which maps the relationship between the constituent elements of man.

Gustav Oehler concludes, “From all this it is clear that the Old Testament does not teach a trichotomy of the human being in the sense of body, soul, and spirit, as being originally three co-ordinate elements of man; rather the whole man is included in the בָּשָׂר and נֶפֶשׁ (body and soul), which spring from the union of the רוּחַ with matter, Ps. 84:2, Isa. 10:18; comp. Ps. 16:9. The רוּחַ forms in part the substance of the soul individualized in it, and in part, after the soul is established, the power and endowments which flow into it and can be withdrawn from it.” [Oehler, p. 151]

Payne elaborates, “Soul néfesh, is generally felt as being a more personal and individual term than rûaḥ, spirit. Man has a rûaḥ, but he is a néfesh: he thinks with his rûaḥ, but the thinker is the néfesh.” If nepeš is an individual it comes to an end with the death of the individual. At death the flesh returns to dust (Gen. 3:19; Ps. 103:14; Job 34:14, 15), for man is but dust and ashes (Gen. 18:27). However, the spirit, rûaḥ returns to the presence of God himself (Ecc. 12:9). The soul nepeš leaves the body at death and continue its ‘existence’ separate from the body (Gen. 35:18; cf. I Kings 17:22 on the rare case of a soul’s return to its body). But death does not mean the body has no permanent significance. It’s full significance becomes clearer later in the Old Testament with the hope for final resurrection (Dan. 12:2).

Sources and References

John Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting: Biblical Anthropology and the Monism-Dualism Debate 2e (Eerdmans, 2000).

Edmond Jacob, Theology of the Old Testament (Hodder & Stoughton, 1958).

Gustav Oehler, Theology of the Old Testament (Zondervan, 1883 1960).

J. Barton Payne, The Theology of the Older Testament (Zondervan, 1962).

Hans Walter Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament (Fortress, 1981).

Next Post: OT Anthropology Between Holism and Dualism. DRLE Pt.2