What Wright Really Said About Forensic Justification and Imputation

Reading N.T. Wright is like eating the Indonesian snake fruit (Salak). Some people find it delicious because of its moist and crunchy sweetness, but others find its slight astringent aftertaste less than appealing. A similar divide is evident among readers of Wright. Wright writes with verve, wit and engaging rhetoric. His friends and critics would acknowledge that it is a pleasure to read him even when he is expounding some of the most difficult and profound issues of historical revelation of Christ and Pauline soteriology. Evangelicals and Reformed scholars welcome Wright’s affirmation of scriptural authority and traditional marriage. They value Wright’s book on the resurrection of Christ which many consider to be the most robust biblical defence on the subject in recent times. His call for kingdom building through social reconciliation and restoration of creation is a vital challenge to Christian mission to be holistic.

Evangelicals nod with hearty agreement as they find Wright using the same language as the Reformers to describe God’s great work of reconciliation of fallen humanity and restoration of fallen creation – covenant, righteousness, forensic justification and inaugurated eschatology. Yet, for all the initial excitement that accompanies the reading of Wright’s captivating prose, the thoughtful reader who has imbibed deeply the spirit of Lutheran and Calvinistic Reformation somehow feels a sense of unease – that while Wright uses the same words as the Reformers, nevertheless he actually means something different; that while there is much agreement between Wright and the spirit of the Reformation, yet there are significant differences in some crucial matters of soteriology. This sense of unease is made worse as Wright does not hesitate to direct his sharp polemics against Reformation scholars who do not agree with him. Sparks ensue from the theological dispute as Wrights detractors return in kind at the polemics directed at them.

The Early N.T. Wright on Present and Future Justification

I have noted in an earlier post how Wright prompted much criticisms because of his infelicitous choice of words when he suggested a future justification of the believer “on the basis of the entire life at the final judgment.

Wright writes, “Present justification declares, on the basis of faith, what future justification will affirm publicly…on the basis of the entire life. [What St. Paul Really Says (Lion Publishing, 1997), p. 129] He elaborates, “The whole point about “justification by faith” is that it is something which happens in the present time (Romans 3:26) as a proper anticipation of the eventual judgment which will be announced, on the basis of the whole life led, in the future [emphasis added] (Romans 2:1-16). [Paul: In Fresh Perspective (Fortress, 2009), p. 57]

Wright’s critics naturally understand him to be teaching that faith + good works = justification, in contrast to Reformed theology which teaches that faith = justification + good works. One cannot miss the uncanny similarity between the teaching of Wright and Rome. More importantly, Wright must be judged to have been unnecessarily restrictive when he insists that justification “was not about how someone might establish a relationship with God. It was about God’s eschatologically definition (both future and present, of who was, in fact, a member of his people.” [What St. Paul Really Said, p. 119]

Accordingly, Peter O’Brien forcefully counters Wright’s view which he judges to be a teaching that undermines Christian assurance.

By suggesting that there are two bases, Christ’s work for us and the Spirit’s work in us, and then “giving sanctification an instrumental role in procuring the final verdict of justification, Wright has significantly compromised the objective…nature of the sinner’s justification by faith alone.” This has the net effect of undermining the actual basis of Christian assurance. One’s justification, however, rests not on works of regeneration or even on faith, but entirely on the substitutionary death of Christ. Certainly this is “embraced by faith and evidence in regenerative works.” But justification is not “an anticipatory announcement on the ground of the subsequent ethical transformation,” nor does it come about “by looking on the judicial aspect of the work of God in justification in unity with the ethical aspect of the work of God in sanctification.” [D.A. Carson, ed., Justification and Variegated Nomism, vol.2, (Mohr Siebeck-Blackwell, 2004), p. 292]

However, the clarifications given by Wright in his later book, Paul and the Faithfulness of God [PFG], show that he shares much with the Reformation tradition. Hopefully, the debate with Wright will become more tempered since he has toned down his polemical language which may have obscured the commonality shared between him and the Reformation. Wright writes that “The people declared to be ‘in the right’ are the people who are incorporated into the Messiah” and that present justification is forensic declarative, and anticipatory of the final declaration at judgment. Wright clearly frames forensic justification in the context of “inaugurated, incorporative, covenantal eschatology” and that “God in a future and final justification will vindicate his righteousness as he rectifies and reintegrates humanity with a restored creation.” [Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Fortress, 2013), p. 943 (PFG)]

The Later N.T. Wright on Forensic Justification

[Lengthy excerpts from the book [PFG] are given below to help readers who do not have easy access to his writings; square brackets denote page numbers].

[935] We thus find, in Paul, ‘covenantal and forensic eschatology’, and, with that, a further depth in the phrase ‘the righteousness of God’. This God will not only act in fidelity to the covenant; when he does so, that will be the means by which he will put all things right, like a judge finally settling a case. The forensic meaning of the divine righteousness thus originated in the covenantal context in the first place (Israel’s belief in the ultimate justice of the one God; Israel’s appeal to that ultimate justice as the source of rescue and vindication), and belongs closely with it. If, of course, the covenantal narrative is confronted with the problem that the covenant people, like everyone else, are sinful and guilty before the divine tribunal, the forensic setting will not only make that clear but also offer the appropriate model for displaying the divine solution.

[936] All these themes point forward to the decisive divine judgment on the last day, in other words, to ‘final eschatology’.

[938] This just [future] judgment (dikaiokrisia, 2.5) will be on the basis of the totality of the life that has been led. God will ‘repay to each according to their works’.

[941] Paul’s vision in Romans 1—8, then, has as its framework the all-important narrative about a future judgment according to the fullness of the life that has been led, emphasizing the fact that those ‘in Christ’ will face ‘no condemnation’ on that final day (2.1–16; 8.1–11, 31–9). The reason Paul gives for this is, as so often, the cross and the spirit (8.3–4): in the Messiah, and by the spirit, the life in question will have been the life of spirit-led obedience, adoption, suffering, prayer and ultimately glory (8.5–8, 12–17, 18–27, 28–30). This is not something other than ‘Paul’s doctrine of justification’. It is its outer, eschatological framework.

[944-945] When Paul speaks about people being ‘justified’ in the present, he is drawing on the framework of eschatological, forensic, participatory and covenantal thought… that in the present time the covenant God declares ‘in the right’, ‘within the covenant’, all those who hear, believe and obey ‘the gospel’ of Jesus the Messiah. The future verdict (point 5) is thus brought forward into the present, because of the utter grace of the one God

[944-945] (i) First, as we indicated above, the verb dikaioo is declarative…The declaration, in other words, is not a ‘recognition’ of ‘what is already the case’, nor the creation of a new character, but rather the creation of a new status…The Greek word for this new status is dikaiosyne. This is what it means for ‘righteousness’ to be either ‘reckoned’ or ‘accounted’ to someone. They possess ‘righteousness’ as a result of the judge’s declaration.

[946] We stress again: this is a declaration, not a description. It does not denote or describe a character; it confers a status. In that sense, it creates the status it confers. Up to that point, the person concerned cannot be spoken of as ‘righteous’, but now they can be and indeed must be. Thus the status of being ‘in the right’, reckoned ‘righteous’, is actually created by, and is the result of, the judge’s declaration. That is what it means to say that the status of ‘now being in the right’, dikaiosyne, has been reckoned to the person concerned.

[948] The first thing to get clear, then, is that the word ‘justification’, within its forensic sense, refers very precisely to the declaration of the righteous God that certain people are now ‘in the right’, despite everything that might appear to the contrary. [ NKW: Question – Is there some significance in the scare quotes of ‘in the right’?]

N.T. Wright’s Rejection of Imputation

Reformation/Reformed scholars agree with Wright’s description of justification as declaration and conferment of status. Indeed, “dikaiosyne, has been reckoned to the person concerned” is what the Reformed theology meant by imputed righteousness. Nevertheless, as in all things academic, there are serious disagreements between Wright and the Reformation, especially in the area of imputed righteousness.

The earlier N.T. Wright wrote, “this time we glance at 1 Corinthians 1:30. There, Paul declares that ‘It is by God’s doing that you are in Christ Jesus, who became for us wisdom from God, righteousness, sanctification and redemption.’ It is difficult to squeeze any precise dogma of justification out of this shorthand summary. It is the only passage I know where something called ‘the imputed righteousness of Christ,’ phrase more often found in post-Reformation theology and piety than in the New Testament, finds any basis in the text. But if we are to claim it as such, we must also be prepared to talk of the imputed wisdom of Christ; the imputed sanctification of Christ; and the imputed redemption of Christ; and that, though no doubt they are all true in some overall general sense, will certainly make nonsense of the very specialized and technical senses so frequently given to the phrase ‘the righteousness of Christ’ in the history of theology.” [What Saint Paul Really Said, pp. 122-123]

Wright further sharpens his polemics against imputed righteousness as he considers it to be a case of category mistake to merge “justification” which declares the objective status with “imputed righteousness” personal moral virtue.

The idea that what sinners need is for someone else’s “righteousness” to be credited to their account simply muddles up the categories, importing with huge irony into the equation the idea that the same tradition worked so hard to eliminate, namely the suggestion that, after all, “righteousness” here means “moral virtue,” “the merit acquired from lawkeeping,” or something like that…Imputed righteousness” is a Reformation answer to a medieval question, in the mediaeval terms which were themselves part of the problem. [N. T. Wright, Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision (IVP, 2009), p, 213]

Wright emphasizes that the Mosaic Law was never given to Israel as a means to earn merit for salvation or righteousness. The way of Israel’s covenant was that the gift of salvation preceded obligation.

It is therefore a straightforward category mistake, however venerable within some Reformed traditions including part of my own, to suppose that Jesus “obeyed the law” and so obtained “righteousness” which could be reckoned to those who believe in him. To think that way is to concede, after all, that “legalism” was true after all—with Jesus as the ultimate legalist. At this point. Reformed theology lost its nerve. It should have continued the critique all the way through: “legalism” itself was never the point, not for us, not for Israel, not for Jesus To think that way is to concede, after all, that “legalism” was true after all—with Jesus as the ultimate legalist. [Ibid., 232]

[951] This is not, however, a matter of the Messiah possessing in himself the status of ‘righteous’, and this ‘righteousness of the Messiah’ somehow being ‘imputed’ to the believer. I understand the almost inevitable pressure towards some such reading, granted the medieval context to which the Reformers were responding, and the pastoral needs which such an idea of ‘imputed righteousness’ is believed to address. But it is not Pauline. (a) Paul never speaks of the Messiah having ‘righteousness’. In the one place (1 Corinthians 1.30) where he comes closest, he also speaks of him having ‘become for us God’s wisdom – and righteousness, sanctification and redemption as well’. So if we were to speak of an ‘imputed righteousness’ we should add those others in as well, which would create a whole new set of doctrinal puzzles. (b) The second half of the apparent ‘exchange’ of 2 Corinthians 5.21 is not about ‘the Messiah’s righteousness’, but about ‘God’s righteousness’; and it is not about ‘imputation’, but about Paul and those who share his apostolic ministry ‘becoming’, that is, ‘coming to embody’, that divine ‘righteousness’ as ministers of the new covenant.492 (c) When Paul does speak of things that are true of the Messiah being ‘reckoned’ to those who are ‘in him’, the focus is not on ‘righteousness’, but on death and resurrection (Romans 6.11). That is actually a much stronger basis for the pastoral application which those who teach ‘imputed righteousness’ are rightly anxious to safeguard. Those who belong to the Messiah stand on resurrection ground.

John Piper Critique of N.T. Wright’s View of Justification-Imputation

John Piper in his book, The Future of Justification: A Response to N.T. Wright (Crossway, 2007) identifies some of the reasons causing Reformed theologians to feel uneasy when they read Wright. [the page citations [ ] given below are taken from this book]

First, Wright has departed from the Reformation with his understanding of justification.

[93] For Wright “justification is not part of God’s work in conversion or the divine action whereby a person becomes a part of the covenant family. Rather, justification is a declaration that a person has been converted and is now, because of faith and God’s effectual calling, in the covenant family. “‘Justification’ is not about ‘how I get saved’ but ‘how I am declared to be a member of God’s people.’” [Paul in Fresh Perspective, p.122]

[94] [Justification] was not so much about ‘getting in’, or indeed about ‘staying in’, as about ‘how you could tell who was in’. In standard Christian theological language, it wasn’t so much about soteriology as about ecclesiology; not so much about salvation as about the church. [What Saint Paul Really Said, p. 119]

Second, Wright offers an ambiguous (and for some, questionable) understanding of the relationship between works and justification. John Piper cites Richard Gaffin’s finely balanced response to Wright’s view of work and justification given in his book.

[116] For Christians, future judgment according to works does not operate according to a different principle than their already having been justified by faith. The difference is that the final judgment will be the open manifestation of that present justification. . . . And in that future judgment their obedience, their works, are not the ground or basis. Nor are they (co-)instrumental, a coordinate instrument for appropriating divine approbation as they supplement faith. Rather, they are the essential and manifest criterion of that faith, the integral “fruits and evidences of a true and lively faith.” [Richard Gaffin, By Faith, Not by Sight: Paul and the Order of Salvation (Paternoster, 2006), p. 98]

[117] Unlike Gaffin, Wright repeatedly refers to works—the entirety of our lives—as the “basis” of justification in the last day. However, Wright also uses the language of judgment and justification “according to works” in a way that inclines one to think that the terms “according to” and “on the basis of” may be interchangeable for him.

Piper acknowledges that there are instances where Wright does come across as a traditional Protestant.

[119] For example, referring again to Romans 2:13 (“the doers of the law . . . will be justified”) he says:

The “works” in accordance with which the Christian will be vindicated on the last day are not the unaided works of the self-help moralist. Nor are they the performance of the ethnically distinctive Jewish boundary-markers (Sabbath, food-laws and circumcision). They are the things which show, rather, that one is in Christ; the things which are produced in one’s life as a result of the Spirit’s indwelling and operation. In this way, Romans 8:1–17 provides the real answer to Romans 2:1–16.7 [New Perspective on Paul, p. 254]

Third, on the one hand, Wright affirms the union of the believer with Christ:

[123] [Christ’s] role precisely as Messiah is not least to draw together the identity of the whole of God’s people so that what is true of him is true of them and vice versa. Here we arrive at one of the great truths of the gospel, which is that the accomplishment of Jesus Christ is reckoned to all those who are ‘in him’.

On the other hand, Wright rejects the Reformation view of the imputation of Christ righteousness:

[124] His understanding of the traditional view is that “Jesus Christ . . .fulfilled the moral law and thus . . . accumulated a ‘righteous’ status which can be shared with all his people.” Thus being in Christ is crucial, in the traditional view, because Jesus has a righteousness that we need, now and at the last judgment, and it is imputed to us when we are united to him by faith alone.

But Wright thinks this is a misunderstanding of Paul, for it misses the point of what Christ’s righteousness is. Wright says, “On my reading of Paul the ‘righteousness’ of Jesus is that which results from God’s vindication of him as Messiah in the resurrection.” In other words, when we think of imputation, we should not think of Christ’s obedience—his moral righteousness, or his fulfillment of the law—but rather his position of being vindicated into a glorious resurrection life after his atoning death. So it is not the “status” of a fulfilled moral law that is reckoned to us in union with Christ, but the status of vindication, that is, covenant membership.

There is indeed a status which is reckoned to all God’s people [this would be the meaning of imputation in Wright’s system], all those in Christ; and this status is that of dikaiosune, ‘righteousness’, ‘covenant membership’; and this covenant membership, in order to be covenant membership, must be a covenant membership in which the members have died and been raised, because until that has happened they would still be in their sins.

Assurance Weakened without Imputation of Righteousness

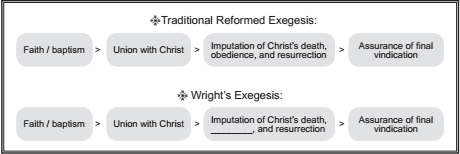

[125] Piper offers the following diagram which identifies the crucial difference between Wright and the Reformation:

Wright rejection of the traditional Reformation/Reformed view of imputation of Christ righteousness has led to ambiguities in his writing about whether Christ righteousness is imputed or really imparted to the believer. More seriously, it obscures the relationship between sanctification and justification which is a matter of grave consequences to assurance of salvation as will become evident in a future post on the theological controversies during the Reformation, “NPP – Regensburg (1541) Redux? Reformation Forensic Justification vs Transformative Justification.”

Piper gives three serious consequences arising from rejection of imputation of Christ’s righteousness (active obedience).

[128-129]

1. It leaves the gift of the status of vindication without foundation in real perfect imputed obedience. We have no perfect obedience to offer, and, Wright would say, Christ’s obedience is not imputed to me, nor does it need to be. He does not believe that this is a biblical category. So we have no perfect obedience as the foundation of our status of vindication (i.e., justification).

2. This absence of a foundation for our vindication, in real perfect obedience, results in a vacuum that our own Spirit-enabled, but imperfect, obedience seems to fill as part of the foundation or ground or basis alongside the atoning death of Jesus.

3. The ambiguity about how works function in “future justification” leaves us unsure how they function in present justification. Wright is emphatic about present justification being by “faith alone”…But calling the present justification an anticipation of the “final justification” while being ambiguous about the way our works function in the “final justification” is not a strong way to assure us that present justification is not grounded in Spirit-enabled transformation.

Piper concludes:

Whatever Wright means by saying the future justification “follows from” our Spirit-led life, he apparently intends for us to distinguish this from justification by faith alone. So again I ask: Does not the effort to call the present justification an anticipation of the final one tend to undermine the truth that present justification is by “faith alone”? He calls this present justification an “anticipation” of future justification, and yet they seem to have two different foundations.

To be fair, Piper has invited Wright to clarify his exact position on this complex issue that can easily be clouded by misunderstanding, “I use the word seem as an invitation to Wright to express himself with more precision if he wants us to understand clearly where he stands.” However, Wright has so far still not responded to this invitation – Wright’s book, Justification: God’s Plan & Paul Vision (IVP, 2009) comes across as a feeble attempt to answer Piper, notwithstanding his excuse that the book is not a “hand-to-hand fighting” piece of work, but that it is only “to sketch something which is more like an outflanking exercise than a direct challenge on all the possible fronts.” (p.9). For the moment, I shall only try to uncover the motives underlying Wright’s rejection of imputation of Christ righteousness.

We note that Wright continues to insist that justification is not about being given a right relationship with God as being members of the church or covenant community. Wright’s contention remains unconvincing since Stephen Westerholm, Mark Seifried, S.J. Gathercole, D.A. Carson and other exegetes have mounted a solid linguistic case for justification to refer to how one is declared to be in right relation with God rather than covenant membership. To be sure, righteousness remains a benchmark for members in the covenant, and God demonstrates his saving righteousness when he fulfills his covenant promise, but this does not justify Wright tenuously equating (1) covenant membership and (2) justification as a declarative speech act or a declaration that one is in right standing before God.

Wright remains adamant in rejecting the idea of imputation since he considers it to be a “confusion [that] goes back to the medieval ontologizing of iustitia as a kind of quality, or even a substance, which one person might possess in sufficient quantity for it to be shared, or passed to and fro, among others.” [PFG 947] However, Wright does not offer an alternative basis for the assurance of salvation, although there seems to be some possibility for it when he refers to the incorporation of the believer into the Messiah without further elucidation. In contrast, the Reformation teaching of the imputation of God’s alien righteousness assures the believer that he may fully and only rely on the sovereign work of God for his salvation, rather than rely on personal obedience (albeit, seen as evidence of the Spirit’s work) that leads him to ultimate vindication.

In any case, Wright’s concerns for assurance appears to be minor as he focuses more on the covenant and covenantal dimensions of sin (one may note from the index of PFG the paucity of references to personal sin, assurance and sanctification by the Holy Spirit). This is undoubtedly due to the influence of Krister Stendhal’s famous essay, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West” (1963). Based on his social concerns, Wright interprets Romans 7, the locus classicus on Paul’s personal and existential struggles with sin under the wrath of God as referring instead to Israel in Sinai and its failure to keep the law.

When the children of Israel came through the Red Sea, they arrived at Sinai and were given the Law. In Romans 7:1-8:11 Paul declares that the renewed people are given the Spirit to do “what the law could not” (Romans 8:3). He argues (through the device of the “I,” speaking of himself as the embodiment of Jewish history) that when the Law was originally given Israel recapitulated the sin of Adam (Romans 7:7-12, looking back to Romans 5:20), that in her continuing life under the Torah Israel finds herself simultaneously desiring the good and unable to avoid the buildup of sin, and that Israel, despite her great vocation, remains “in Adam” (Romans 7:1-6, 13-25). God, however, has dealt with sin and given new life, to those who share the resurrection of Christ through the Spirit (Romans 8:1-11). [Bible Review, June 1998]

Whether Romans 7 should be interpreted as personal or social will continue to be hotly contested between scholars, but one can be sure that a Wrightian interpretation would have offered no help to the early Martin Luther [notwithstanding his last sentence in the previous quotation] when he was tormented by a lack of assurance of salvation, even though he believed in the Roman Catholic concept of infused righteousness through union with Christ. It seems that the NPP-Wrightian approach exacts a rather high price – the undermining of the precious insight gained by Luther in the Reformation that believers are assured of their salvation precisely because the righteousness that enables them to stand rightly before God rests not on their own righteousness but on the alien righteousness of Christ imputed to them by virtue of their union with Christ (Rom. 5:12-19 and 2 Cor. 5:21).

Concluding Remarks on N.T. Wright’s Methodology

Wright rejection of imputation is also a consequence of his methodology as he refuses to go beyond analyzing the descriptive language of historia salutis or salvation history (the domain of biblical theology which looks at the progressive stages of God’s work of salvation), and seriously engaging with the logic of ordo salutis (the domain of systematic theology which looks at the logical relations between the various aspects of God’s salvation). Consequently, for all his brilliant intellect, he ends up with a confusing coalescence of concepts when he tries to explain the relationship between sanctification, justification, regeneration and vindication-glorification. [See http://ntwrightpage.com/Wright_Justification_Biblical_Basis.pdf] In passing it may be noted that Wright’s refusal is akin to Muslim debaters who insist on rejecting the doctrine of Trinity unless they are given bible verses that have direct reference to the word ‘Trinity’.

However, Wright’s refusal is an unnecessary impoverishment of Christian theological discourse on soteriology. D.A. Carson notes that while Paul speaks exclusively of us being reconciled to God; the apostle never speaks of God being reconciled to us. Nevertheless, there is a long and honorable heritage within theological discourse does not hesitate to speak of God being reconciled to us. Carson concludes,

The biblical scholar who is narrowly constrained by the exegetical field of discourse may be in danger of denying that it is proper to speak of God being reconciled o us; the theologian who is not exegetically careful may be in danger of trying to tie the notion that God is reconciled to us to the wrong passages. [D.A. Carson, “The Vindication of Imputation: On Fields of Discourse and Semantic Fields,” in Justification: What’s at Stake in the Current Debates, ed., Mark Husbands and Daniel Treier (IVP, 2004), pp. 49-50]

Carson presses his point with another example, “Strictly speaking, there is no passage in the New Testament that says our sins are imputed to Christ…So why should a scholar who accepts that Paul teaches that our sins are imputed to Christ, even though no text explicitly says so, [notwithstanding the usual texts of Gal. 3:13 or 2 Cor. 5:19-21] find it so strange that many Christians have held that Paul teaches that Christ’s righteousness is imputed to us, even though no text explicitly say so.” [Carson, ibid., p. 78]

The great NT scholar, Leon Morris long ago suggested a way to bridge these distinguishable but inseparable domains of theological discourse:

In view of plain statements like these [Romans 4: 3, 5] it seems impossible to hold that Paul found no place for the imputation of righteousness to believers. On the other hand he never says in so many words that the righteousness of Christ was imputed to believers, and it may fairly be doubted whether he had this in mind in his treatment of justification, although it may be held to be a corollary [emphasis added] from his doctrine of identification of the believer with Christ.

But, if our primary idea is correct, then the basic thought in righteousness is of a standing with God,” and we should think of a status conferred on men by God on the grounds of the atoning work of Christ. There is a sense in which it can be said to be imputed, for it is in no sense an ethical righteousness attained by the believer by the performance of good works, but rather a gift from without, from God. But it seems preferable to regard the idea of conferred status as primary, rather than to look at the whole subject through the comparatively few passages which speak of imputation [Leon Morris, The Apostolic Preaching of the Cross, 3e (Tyndale Press 1965), p. 282].

In this regard, so long as Wright insists on restricting his domain of discourse to historia salutis (biblical theology) he will fail to appreciate, much less be convinced by the Reformed teaching that justification and imputed righteousness through union with Christ provides a legitimate and comprehensive framework that highlights the fundamental problem of sin under the wrath of God, and captures adequately (certainly more adequately than NPP) the gift of righteousness of God and the full benefits of union in Christ.