*This article was published originally in The Malaysian Insight (25/11/2017): Translating the Malay Bible: CLJ Needs to Get the Historical Facts Right!

Image Above: Ruyls-Dutch-Malay-Bible 17C

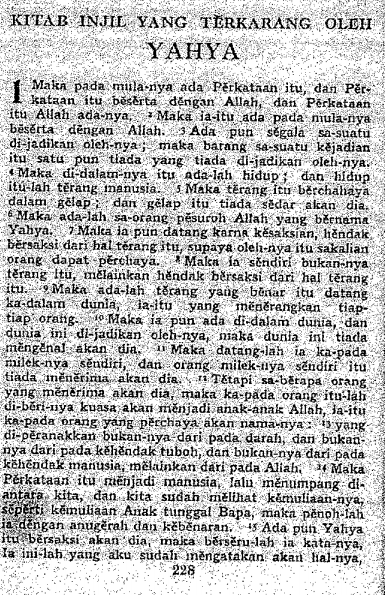

Image Above: Gospel of John Shellabear Bible Originally Printed 1912 (Image from 1949 reprint)

Recently, Concerned Lawyers for Justice (CLJ) argued that the Christian community should work closely with Dewan Bahasa & Pustaka (DBP) to correct purported errors in the current translation of the Malay Bible. Suggestions to improve existing translations of the Bible is in line with the ethos of the Christian enterprise of Bible translation which is an ongoing exercise undertaken by Bible societies all over the world.

However, CLJ’s proposal to allow DBP to prepare an authoritative translation of the Malay Bible is unacceptable. The reason is because given the terms and conditions for DBP’s involvement, the proposal amounts to an illegitimate restriction of religious freedom and infringement of the autonomy of the institutions of the Christian community. It is a violation of the integrity of Christian faith as it will lead to an imposition of Islamic religious beliefs on its sacred Bible.

CLJ declares that it seeks to “to set the records straight” so that the Christian community will be persuaded to set aside its prejudices and work with DBP. Unfortunately, CLJ’s argument is prejudiced against the Christian community as it relies on a skewed reading of historical facts.

First, CLJ misuses the article written by Robert Hunt to stigmatize the Malay Bible as a work done by incompetent translators who know but a little “more than a smattering of Malay.” It suggests that the early translators did not benefit from studying Malay literature. This criticism must be taken in its proper context.

In particular, the diversity of Malay dialects from Aceh to Ambon in the early Malay translation should not be taken to be a sign of linguistic incompetence or confusion. The first translators of the Bible into Malay were aware that Christians who used Malay came from different backgrounds, ranging from “mardijkers” (former slaves) to civil servants. The Christian translators were sensitive to how language assumes different socio-linguistics at different stratas of society. The problem for these translators in the 17th and 18th centuries was this: should they opt for ‘high’ Malay language used in the learned circles, or popular Malay used by the ordinary people as their lingua franca? Hence, Christians have produced both formal translations as well as dynamic-equivalence translations of the Malay Bible. Some translators like Valentijn in the Molukkas chose to produce a translation in popular Malay, while Leijdekker preferred the ‘high’ Malay.

Even if it is granted that some of the early translators could have been more competent in the Malay language, the same charge of incompetence cannot be levelled at William Shellabear who consulted extensively with Malay language and religious experts, not least Guru Sulaiman bin Muhammad Nur, with whom he jointly published several classical works including Kitab Kiliran Budi and Hikayat Hang Tuah.

Christians are themselves aware that the earlier translations of the Bible could be improved. Indeed, Christians have systematically undertaken revisions of the Malay Bible to ensure its accuracy and comprehension for new readers using a dynamic and changing language like Malay. As a result, all shortcomings identified in the earlier translations have being remedied in the new translations of the Malay Bible.

That there will always be contestations in any translation enterprise is a given, and this is aptly captured by the Malay proverb, “Tiada gading tanpa retak?” It would be good to be reminded at this juncture that for the Christian community it is the Hebrew and Greek texts that have the final authority to settle any theological interpretation and translation issue. Referring to these Hebrew and Greek Texts would normally settle the translation ambiguity in question.

Second, CLJ gives the impression that the early translators were insensitive to concerns expressed by Munshi Abdullah who felt that Leidekker’s Bible “was not idiomatic.” Furthermore, “Munshi also objected to the various biblical phrases in Malay, like that of “Kerajaan Syurga” (Kingdom of Heaven), “Mulut Allah” (Word of God), “Anak Allah” (Son of God), and so on and so forth.”

There are unavoidable disagreements in any translation. However, it should be noted that Munshi Abdullah’s concern was about the propriety of using the name of God in the “possessive” or “genitive” (e.g. “Allah-ku” sounds odd to readers familiar with Arabic). It is significant that Shellabear decided to use Allah in his translation after the discussion on the appropriateness of using the possessive with the name of God.

More importantly, contemporary Indonesian/Malay linguistic experts involved in translation of the Malay Bible, based on empirical observations, rightly conclude that the use of the possessive (words like “Allahku” or “Selangorku”) no longer seem awkward today, at least to the Malaysian/Indonesian Malay-speaking Christians who number more than 30 million. The scruples raised by Munshi Abdullah may be of some historical interest, but they should not be determinative in Bible translation today.

A closer reading of the historical facts in context can only lead to the conclusion that CLJ is guilty of misquoting and misappropriating Robert Hunt. It is not the case of “setting the record straight” so much as slanting the record against the Christian community.

Third, CLJ’s argument that Christian usage of Allah must conform to views of experts represented by “authoritative works” like Aqa’id al-Nasafi and Aaja Ali Haji is fallacious. CLJ ignores the fact that the meaning of a religious words must be defined by how each particular religious community uses the word in its own context. The purpose of lexicography which defines meaning of words in dictionary should be descriptive rather than legislative – except in the case where linguistic experts follow the diktat of totalitarian rulers like Hitler or Stalin.

The Malay Bible is the Christian holy text and its doctrine and specific teaching about God as unity in trinity should be treated with utmost respect, regardless of whether one agrees with it or not. Furthermore, Christians are not pretending to be teaching Islamic theology from the Malay Bible. As such, CLJ’s insistence that Christian usage of its religious terms conform to Islamic teachings amounts to an intolerable imposition of Islamic theology onto the Christian community.

Fourth, while the Christian community is in principle open to consulting DBP when it prepares a new translation, it finds the terms of cooperation suggested by CLJ to be unreasonable and unacceptable. CLJ assures the Christian community that its religious autonomy will be maintained. However, in reality CLJ is suggesting that the Christian community surrenders its autonomy to DBP. For example, CLJ asserts that “the board (of DBP) shall be the sole coordinating authority [emphasis added] pertaining to composing, devising and standardising of terminologies in the national language.” Unsurprisingly, CLJ proposes a working arrangement with DBP which envisages the Christian community “being magnanimous and admitting to errors in the translation of certain terms, and in submitting to the authority of experts of the national language to determine the correct and accurate terms to be used.”

The proposal by CLJ is evidently specious if we set its proposal in the context the present controversy. Its logic can only lead to an objectionable outcome: (1) DBP is the sole authority in determining the usage of Malay words, (2) The Christian use of Allah in the Malay Bible is inconsistent with the authoritative texts recognized by DBP (and CLJ), (3) Christians should thereby submit to DBP’s directive to stop using Allah in the Malay Bible.

Fifth, the logical outcome of the unequal working relationship proposed by CLJ demonstrates that there is no justice in CLJ’s proposal, not least because it requires the Christian community to submit to an external authority that does not share its beliefs. One thing is clear: CLJ is not simply asking the Christian community to consult or work with DBP. In effect, it is asking the Christian community to submit to DBP. After all, CLJ asserts, “DBP, therefore, is in the prime position to arbitrate as to whether such a claim is true or not, and whether the usage of the term “Allah” is accurate, semantically and linguistically.”

In assigning of the power of arbitration to DBP, CLJ contradicts its earlier acknowledgment that “translation of a religious canon is a humongous” which would require wide ranging and extensive expertise. With all due respect, DBP does not have the required expertise in Bible translation and whatever expertise it may have does not compare favorably with the expertise possessed by the translation experts in the Christian community. Truth be told, the ‘experts’ who represent the government in the current court dispute on the Allah issue have not displayed competence in the original languages of the Bible. They seem unable to understand the nuances in interpretation when Christians address their God as Tuhan-Allah (Yahweh-Elohim) etc. Given this evident lack of expertise, it is unreasonable and unjust to ask the Christian community to submit to their authority when the Christians’ own expertise in understanding and translating its religious text is far superior to that of DBP

CLJ may assure the Christian community that its proposal is not about claiming ownership of the Allah word. Nevertheless, after considering its proposal objectively and carefully, it can only be concluded that it will bring ill consequences to the Christian community. Following CLJ’s proposal would allow DBP to regulate and restrict how Christians may address their God in worship and prayer. It amounts to an imposition of Islamic theology onto the Malay Bible. It undermines the religious autonomy of Christian institutions which is enshrined in the Federal Constitution. Most important of all, it forces Malay-speaking Christians to dishonor the spiritual heritage of their forefathers who have been calling upon their God as Allah for centuries.

Published originally by The Malaysian Insight, Translating the Malay Bible? CLJ Needs to Get the Historical Facts Right! 25/11/2017

—————————–

The above post was written in response to an article by the Concerned Lawyers for Justice (CLJ) published earlier in The Malaysian Insight (21/11/2017):

“Setting the Record Straight on Dewan Bahasa’s Jurisdiction over Malay Bible”

OVER the course of the judicial review hearing at the Kuala Lumpur High Court on November 15 concerning the use of the holy word “Allah” by certain Christian publications in the Malay language, lawyer Mohamed Haniff Khatri Abdulla was reported to have said that Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) should be the body to prepare the Malay-language Bible to correct Christians’ usage of the term “Allah”, and that the text should be sent to the Christian community for approval.

Such a suggestion was met with vehement criticisms by political figures and Christian leaders, who demanded that Mr Haniff apologise for having uttered such a statement.

While the Concerned Lawyers for Justice (CLJ) understands and appreciates the premise of Mr Haniff’s argument, i.e. DBP being the public institution vested with the statutory power and duty as the guardian of the national language, CLJ is mindful that translating a religious canon is a humongous task that requires far more than mere expertise and authority on one particular language alone.

It also requires a deep understanding of the creed of that religion, its theology and traditions, apart from a strong grasp of the history and context pertaining to its teachings, with thousands of years of scholarship, and not to mention, a mastery of the language of the original text.

For this reason, Article 11(3) of the Federal Constitution appropriately provides that every religious group shall have the right to manage its own religious affairs, as a form of protection against unwarranted interference by those in power. And, the suggestion made by Mr Haniff, with due respect, would not stand in the face of such a clear constitutional safeguard.

Be that as it may, CLJ is of the opinion that DBP still has a crucial role to play to untangle the current controversy, albeit in a much more limited scope than to take over the task of translating the Bible (which it has no business meddling in).

This could be seen from the fact that in the attempt to justify the usage of the holy name “Allah”, the Christian community contends that the word is the correct translation of the word “God” in the Malay language, and that it has purportedly been used in Christian publications since as early as the 17th century.

DBP, therefore, is in the prime position to arbitrate as to whether such a claim is true or not, and whether the usage of the term “Allah” is accurate, semantically and linguistically.

This is in line with Section 6 of the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Act 1959, which provides that “the board (of DBP) shall be the sole coordinating authority pertaining to composing, devising and standardising of terminologies in the national language”.

The suggestion of correcting errors in the translation of certain terms in canonical text, such as the Bible, need not necessarily be perceived as an attempt to meddle in the Christian religion, if one were to look into the academic article written by Robert A. Hunt, titled “The History of the Translation of the Bible into Bahasa Malaysia (sic)”.

There, the author stated that “(e)arly translators (of the Bible) learned Malay in places as diverse as Ache and Ambon, usually without the benefit of studying Malay literature”, one of whom, John Stronach, was said to have known but a little “more than a smattering of Malay”.

Such translations prepared by persons who are not competent in the Malay language must surely be open to be criticised and corrected.

The author then went on to narrate how during the 1800s, missionary societies, in particular the London Missionary Society (LMS), attempted to produce the Malay translation of the Bible.

“The story of the LMS efforts to produce the Malay-language Bible begins with an interview between Milne and one of his first language teachers, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, more commonly known as Munshi Abdullah… In that interview, Abdullah was asked to give an opinion on Leidekker’s Bible. He confirmed what Milne no doubt suspected: that this Bible was not idiomatic and had many strange words.”

At one point, the author even noted that Munshi objected to the various biblical phrases in Malay, like that of “Kerajaan Syurga” (Kingdom of Heaven), “Mulut Allah” (Word of God), “Anak Allah” (Son of God), and so on and so forth.

As Hunt himself acknowledged at the end of his academic article, “there may be the need for further new translations”. It is therefore imperative that the Christian community in Malaysia take serious consideration to do what needs to be done in order to do justice not only to the Malay language, but also to their own scriptures.

There is no shame in being magnanimous and admitting to errors in the translation of certain terms, and in submitting to the authority of experts of the national language to determine the correct and accurate terms to be used.

In translating key theological terms, such as the holy name “Allah”, great care must be taken to refer only to authoritative works, from those whose expertise in the Malay language has been duly recognised.

This would include the likes of the oldest known Malay manuscript, the Aqa’id of al-Nasafi (1590), wherein it is affirmed that the holy name “Allah” in the Malay language refers strictly to “the One… (who)… is neither accident nor body, nor atom… (who) is not formed nor bounded nor numbered (that is, He is not more than one), neither is He portioned nor having parts nor compounded”, the definition of which is clearly incompatible with Christians’ concept of trinity.

Another such definition can be seen from that accorded by Raja Ali Haji (who died in 1873), who is considered the first authoritative lexicographer of the Malay language. His detailed definition of the holy name “Allah” in his Kitab Pengetahuan Bahasa (The Book of the Knowledge of Language) could not be more irreconcilable with that of the trinity.

In the above light, one would suggest that the Christian community engage and work closely with DBP, to correct what needs to be corrected in the current translation of the Bible, while maintaining their religious autonomy on the actual translation work.

It must be said that it is unfortunate that the matter has been brought yet again to public attention via a court case as a fully blown constitutional challenge. In the past, this has caused bitter divisions and hatred within our multireligious society, and will continue to do so, unless it is approached very carefully and responsibly.

It is in this light that it becomes all the more important that one must never lose sight of the underlying scope: that the objection is, and always has been, specifically against the alteration of the meaning of the holy name as understood in the Malay language, not Arabic, not English, not any other language.

And, the reason is fear of an unwarranted shifting of the firmly rooted theological concepts emanating from it.

Never has it been about claiming ownership of the word, as some quarters have relentlessly tried to simplistically portray, and neither has it been to prevent Christians from freely professing their religion.

* Concerned Lawyers for Justice is a civil movement comprising lawyers who are concerned about the state of the Malaysian nation.

Press Statement by the Christian Federaion of Malaysia (CFM)

CFM - Al-Kitab a patrimony of Christians - STATEMENT - 20 Nov 2017

DEAR DR. KAM-WENG: YOUR SCHOLARLY AND FIRM REBUTTAL OF CLJ’S PRESUMPTUOUS AND BIASED PROPOSAL IS DEEPLY APPRECIATED. THEY DO NOT KNOW THEMSELVES, AND WHAT THEY ARE SAYING. KEEP UP YOUR GREAT WORK. GOD ABIDES.

KS