High Court quashes govt’s 1986 ban on ‘Allah’ use by Christians, affirms Sarawakian Bumiputera’s right to religion and non-discrimination

10 March 2021 by Ida Lim

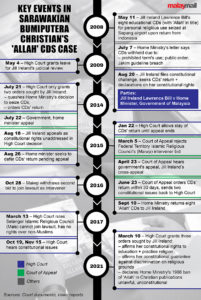

KUALA LUMPUR, March 10 ― The High Court today ruled that the Malaysian government’s directive issued in 1986 with a total ban on the use of the word “Allah” in Christian publications is unconstitutional and invalid, and also declared orders to affirm Sarawakian Bumiputera Christian Jill Ireland Lawrence Bill’s right to not be discriminated against and practise her faith.

Justice Datuk Nor Bee Ariffin, who has since been elevated to be a Court of Appeal judge, granted three of the specific constitutional reliefs sought by the Sarawakian native of the Melanau tribe.

The three orders granted by the judge include a declaration that it is Jill Ireland’s constitutional right under the Federal Constitution’s Article 3, 8, 11 and 12 to import the publications in exercise of her rights to practise religion and right to education.

The other two declarations granted by the judge today are that a declaration under Article 8 that Jill Ireland is guaranteed equality of all persons before the law and is protected from discrimination against citizens on the grounds of religion in the administration of the law ― specifically the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 and Customs Act 1967), and a declaration that government directive issued by the Home Ministry’s publication control’s division via a circular dated December 5, 1986 is unlawful and unconstitutional.

The order today means that the government’s long-standing absolute ban in the 1986 circular on the use of the word “Allah” in Christian publications in Malaysia has been declared invalid by the court.

In delivering her lengthy decision today that took over 90 minutes to read out, the judge said this was the first time the validity of the 1986 government directive — which totally banned the use of four words including “Allah” in Christian publications in Malaysia — has been challenged in the courts.

The judge noted that the Attorney General’s Chambers, which represented the home minister and government in Jill Ireland’s case, had argued that the 1986 directive was a “Cabinet decision which relates to government policy at that point in time”.

The judge then went through the process that was taken before the 1986 directive was issued by the Home Ministry, noting that there was a May 19, 1986 letter from the prime minister at the time to the home ministry’s secretary-general that stated the Cabinet’s assigning of the deputy prime minister to determine the words that were permitted to be used and prohibited to be used by the Christian religion.

The judge then cited the then deputy prime minister’s May 16, 1986 memo addressed to the prime minister, listing 12 words that can be used in the Alkitab (or the Christians’ holy book in Bahasa Malaysia or Bahasa Indonesia), and four words including “Allah” that cannot be used in the publication, along with the condition that the cover of the books carry the words “Untuk Agama Kristian” (For the Christian religion).

Based on court documents previously sighted by Malay Mail, the prime minister and deputy prime ministers then were Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Tun Ghafar Baba.

The judge then said the then deputy prime minister’s May 1986 note became the Cabinet’s policy decision on words allowed to be used in Bahasa Malaysia Christian publications, noting that the government directive was then issued seven months later in December 1986 and signed by an officer in the Home Ministry’s publication control division on behalf of the home ministry’s secretary-general.

The judge noted that the December 1986 directive was not signed by the home minister.

The judge said, however, there was a “marked discrepancy” between the Home Ministry’s December 1986 directive and the Cabinet policy decision.

The judge noted that the government directive imposed conditions on the use of the 12 words and placed a total ban on the use of the four words in Christian publications “for reasons best known” only to the Home Ministry’s publication control division, while the Cabinet policy decision in the deputy prime minister’s note did not put a total ban on the use of the four words as such words could be used if the condition to specify “Untuk Agama Kristian” on the publication’s cover page was fulfilled.

“In my view, on the true and proper construction of the prime minister’s letter and deputy prime minister’s note, the Cabinet policy decision did not impose a total ban on the four words,” she said, referring to the four words including “Allah”.

Among other things, the judge also said there was no evidence brought to court to show that the Cabinet changed its decision or endorsed the version in the 1986 directive, concluding that the 1986 directive was “inconsistent” with the Cabinet policy decision.

The judge noted that Printing Presses and Publications Act (PPPA) 1984’s purpose is only to control “undesirable publications”, and that it does not grant powers to the home minister to issue prohibitions such as those in the 1986 directive.

“In this present case, the minister has not acted according to the law by wrongly giving himself jurisdiction to act by misconstruing the PPPA,” the judge said.

The judge held that Jill Ireland is entitled to the declaration sought for the 1986 directive to be invalidated, noting that the 1986 directive was not authorised to be issued under the PPPA and concluding that it was “unlawful” and a “nullity”.

The judge said the decision to issue the 1986 directive was irrational as it totally disregarded that it would be in direct conflict with previous gazetted government orders. A 1982 government order had permitted the use of Alkitab in churches.

“It is my finding that the imposition of a total ban, total prohibition on the use of all four words, the impugned directive has not passed the Wednesdbury test of reasonableness,” the judge said, adding that the home minister’s decision over the 1986 directive is “irrational and perverse”.

The judge also said the government’s use of “public order” to justify the 1986 directive could not be justified, noting that there was no evidence shown in court of “adequate, reliable and authoritative” proof of any disruptions or potential disruptions to public order when the 1986 directive and 1986 Cabinet policy decision were made.

The judge said the only reason given by the home minister then — Tan Sri Syed Hamid Albar — in an 2010 court affidavit for the prohibition of the use of the word “Allah” was the alleged impact of a 2009 court decision in the case of the Catholic weekly Herald, which had purportedly led to disturbance of public peace.

But the judge pointed out that the home minister’s reasons were based on an issue that came after the 1986 policy decision and directive were made, noting that the decisions should be made based on facts available to the decision-maker at the time the decision was made.

The judge went on to note that the use of the word “Allah” by Bahasa Malaysia-speaking Christians for generations has not led to public order being disrupted in Malaysia.

“It is not disputed that Bahasa Malaysia has been the lingua franca for the native people of Sabah and Sarawak living in their home states and Peninsular Malaysia,” she said, noting that this had not been rebutted in court.

“It cannot be disputed that the Christian community of Sabah and Sarawak has been using the word ‘Allah’ in Bahasa Malaysia for the word ‘God’ for generations in the practice of their religion, in their profession and practice of the Christian faith.

“It is also established that the word ‘Allah’ that has been used has not caused problems of public order,” she added.

“The evidence of the use of the word ‘Allah’ by the applicant (Jill Ireland) and the Christian community in Sabah and Sarawak over 400 years cannot be ignored,” she said, noting evidence raised in court of Christian publications in Malay dating back to the 1600s.

The judge also noted that three Muslims had in court affidavits stated that they were “not confused by the use of the word ‘Allah’” by non-Muslims, noting that the government did not produce testimony from anyone to say that they were confused or had misunderstanding when Christians used the word “Allah”.

Considering the evidence before the court as a whole, the judge said that the grounds of public order cited to issue the 1986 directive was not supported.

“The first respondent’s (home minister’s) reliance on public order and threat of public order in making the impugned directive is irrational and perverse,” the judge concluded.

When looking at the constitutional issues in Jill Ireland’s case, the judge said that Article 3 of the Federal Constitution — which states Islam to be the religion of the federation and allows other religions to be practiced in peace and harmony — does not override or extinguish the constitutional rights of Article 10, 11 and 12.

The judge highlighted that a clause in Article 3, namely Article 3(4) states that nothing in Article 3 derogates or takes away from any other provisions in the Federal Constitution.

The judge also said the only powers to restrict religious freedom are in Article 11(4) and Article 11(5) of the Federal Constitution, saying however the Printing Presses and Publication Act is not a law that comes under the Article 11(5) category.

Under Article 11 which covers the right to freedom of religion including to profess and practice one’s own faith, Article 11(4) provides that state laws may control the spread of any religious doctrine among Muslims, while Article 11(5) states that Article 11 does not authorise any act contrary to any general law relating to public order, public health or morality.

Among other things, the judge noted that religious freedom in Article 11 is not subject to the special powers under Article 149 for Parliament to make laws, and that Article 150(6) provides that freedom of religion cannot be restricted by Emergency laws.

The judge said the sole basis for the government’s confiscation of Jill Ireland’s eight compact discs containing the word “Allah” in their titles was the exercise of powers under the PPPA in reliance of the prohibition imposed by the 1986 directive.

“The minister had unlawfully issued the impugned directive — under the PPPA — which has been found to be a nullity and had unlawfully exercised powers under the PPPA to impose the directive.

“The minister in my view has no power to deprive a person of his right to practise and profess his religion, which is guaranteed under Article 11 of the Federal Constitution and therefore the act of the minister to impose a prohibition to import the eight CDs with the impugned directive would be inconsistent with Article 11 of the Federal Constitution, unless the applicant’s (Jill Ireland’s) action was shown to go beyond what can be normally regarded as practise and profession of her religion,” the judge.

The judge said it was not disputed that the eight CDs were for Jill Ireland’s own religious education and there was no evidence to show that her action had gone beyond what can be normally regarded as her practice and profession of her religion, further noting that the right to practice and profess one’s religion should include the “right to have access to religious material”.

The judge disagreed with the government’s arguments that the declarations sought by Jill Ireland to uphold her constitutional rights were hypothetical and premature.

“She has been deprived before and there is no assurance that it may not happen again, the declaratory order will eliminate the uncertainty and the applicant having to live under a cloud of fear,” the judge said.

“In conclusion, based on the foregoing, I grant the applicant’s declarations in paragraph c), paragraph d), paragraph d)B),” the judge said when listing the three court declarations to be granted to Jill Ireland.

As this was a public interest matter and as Jill Ireland’s lawyers said they were not seeking for costs, the judge did not give any order for costs to be paid to Jill Ireland by the government.

Lawyers Lim Heng Seng, Annou Xavier and Tan Hooi Ping today represented Jill Ireland, while the home minister and government were represented by senior federal counsel Shamsul Bolhassan.

Lawyer Mohamed Haniff Khatri Abdulla appeared for the Federal Territories Islamic Religious Council (Maiwp) and the Selangor Islamic Religious Council (Mais) who were both amicus curiae, while lawyers holding watching brief today were Andrew Khoo for the Christian Federation of Malaysia, Rodney Koh Ngiap Teik for SIB Semenanjung, Cyrus Tiu Foo Woei for the Bar Council, and Datuk Simon SC Lim for the MCA.

Previously during the High Court hearing, lawyers had also held watching brief for the Bible Society of Malaysia, Synod of the Diocese of West Malaysia, Sabah Council of Churches, Association of Churches of Sarawak, SIB Sarawak, SIB Sabah, and National Evangelical Christian Fellowship.

Background of the case

The Bahasa Malaysia-speaking Jill Ireland filed her lawsuit almost 13 years ago after the Home Ministry seized eight educational compact discs (CDs) containing the word “Allah” meant for her personal use at the Sepang LCCT airport upon her return from Indonesia.

Following the May 11, 2008 seizure, Jill Ireland filed for judicial review in August the same year against the home minister and the government of Malaysia.

The High Court had in July 2014 ruled that the Home Ministry was wrong to seize the CDs and ordered that they be returned, but did not address the constitutional points then.

Jill Ireland finally received her CDs in September 2015, months after the Court of Appeal had in June 2015 directed the Home Ministry to do so.

At the same time, the Court of Appeal in June 2015 sent two constitutional issues back to the High Court to be heard, namely a declaration that it is her constitutional right under the Federal Constitution’s Article 11 to import the publications in exercise of her rights to practise religion and right to education, and a declaration under Article 8 that she is guaranteed equality of all persons before the law and is protected from discrimination against citizens on the grounds of religion in the administration of the law ― specifically the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 and Customs Act 1967).

The High Court later heard the constitutional issues over two days in October and November 2017, but the decision which was initially scheduled to be delivered in March 2018 has been deferred several times over the years, due to various reasons such as both sides seeking resolution outside the court and also the movement control order.

The decision was finally delivered today.