Philosophical and Social Origins of Identity Politics and the LGBTQ Sexual Revolution. Part 2.

Philosophical and Social Origins of Identity Politics and the LGBTQ Sexual Revolution. Part 2.

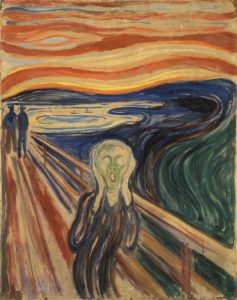

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

W.B. Yeats, The Second Coming

A) Loss of meaningful sacred order and providence

Since antiquity, people acknowledged that there is a natural order of law and morals. Life is best lived when it is lived in accordance with the requirements of natural order. Among the Greeks, the Stoics taught that man must live in harmony with the rational and purposive order in nature. Ancient Israel also acknowledged a natural order, one that is implanted into creation by the Creator. According to the sages of ancient Israel, knowledge of God comes from experiencing God’s activity in the world. Faith in God’s providence means trusting in the reliability of the creation which the benevolent God has ordered to support human life and guide man in his moral knowledge and action. Gerhard von Rad explains, “This order [of creation] was, indeed, simply there and could, in the last resort, speak for itself. The fact that it quietly but reliably worked towards a balance in the ceaselessly changing state of human relationships ensured that it was experienced over and over again as a beneficent force. In it, however, Yahweh himself was at work in so far as he defended goodness and resisted evil. It was he who was present as an ordering and upholding will in so far as he gave a beneficent stability to life and kept it open to receive his blessings.”1Gerhard von Rad, Wisdom in Israel (SCM, 1972), pp. 191-192.

John Calvin is building on the insight of the sages of ancient Israeli when he declares that the world is a theatre for God’s glory and represents his endowment for men’s welfare: “The whole order of this world is arranged and established for the purpose of conducing to the comfort and happiness of man” (Commentary Psalm 8:6). These creation orders are reliable because God instituted them for the welfare of man. However, fallen humanity persistently violates the moral order. As such, God establishes natural law as the “bridle of providence” to reign in disorder in all human relationships and institutions. (Institutes, 2.3.3). That is to say, God as the author of natural law has imparted man with innate knowledge of the precepts of natural law, which if followed, will restraint evil and foster good relationships which are essential for the proper function of a harmonious social order.

Perhaps the idea of creation order and natural law was taken for granted in the pre-technological world because the natural world was perceived to be a stable and unchanging order, in contrast to the frailties of human lives and the ever-changing vicissitudes of human society. Furthermore, if God establishes the orders of the world for the benefits of man, then a fulfilling and flourishing life results when one lives in harmony or in conformity with the orders. Such an outlook is described as “mimesis” – “A mimetic view regards the world as having a given order and a given meaning and thus sees human beings as required to discover that meaning and conform themselves to it.”2Carl Trueman, The Rise of the Modern Self (Crossway, 2020), pp. 39-42. Trueman’s comments on “mimesis” and “poesis” are drawn from Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self (Harvard UP, 1989), pp. 266-284.

The mimetic view of the world made sense in medieval European agrarian society. Since farmers were not in control of the environment or the weather, the best way to ensure a good harvest was to adapt their agricultural methods (local irrigation and terrace farming) to be aligned with the environment and to time their sowing and harvesting in sync with the changing seasons. However, with the benefits of science and technology such as fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation water supplied by massive dams, farmers today understandably think they have the power to manipulate nature to serve their own purposes. Hence the modern imaginary is one of poiesis which “sees the world as raw material out of which meaning and purpose can be created by the individual.” Modern man no longer seeks to live a good and godly life based on conforming to God’s normative order embedded in creation. He would rather seek to inhabit the world as an agent of technological innovations to master and exploit the environment. This new vision of human agency actively shaping the world has become the basis for the pursuit of a good life.3Charles Taylor, The Secular Age (Belknap Press, 2007), pp. 97-99]

The consequence of the triumph of man over nature is that the idea of sacred order and providence has no relevance to modern man. Carl Trueman applies Philip Rieff’s insight to sharpen the contrast between the pre-technological world (“First and second world”) with the modern world (“Third World”). According to Rieff, first and second world envisage morality to be based on a stable sacred order. In contrast, the modern world dispenses with the idea that morality is rooted in the sacred order as implausible since nothing is perceived to be stable in a rapidly changing technological world. There is no moral imperatives rooted in anything sacred. In short, the modern world is bereft of foundations to support and legitimize the moral order. Trueman emphasizes that “Rieff’s central point here is that the abandonment of a sacred order leaves cultures without any foundation. The culture with no sacred order therefore has the task – for Rieff, the impossible task – of justifying itself only by reference to itself. Morality will thus tend toward a matter of simple consequentialist pragmatism, with the notion of what are and are not desirable outcomes being shaped by the distinct cultural pathologies of the day.”4Trueman, Rise and Triumph Modern Self, pp. 76-77.

B) Modernity and Fluid Identity

Social cohesion depends on a variety of supportive social networks which give individuals a sense of belonging as they navigate increasingly complex and changing social landscapes. These networks include social clubs, civic organizations, community centres, etc. which bring together people of different races, religions and social classes to foster a more egalitarian and inclusive society. These social institutions serve as traditions or repositories of moral and spiritual resources which shape the identities of individuals and guide their moral decisions and life choices, such as career paths, spiritual practices and priorities of life.

However, these institutions and traditional networks of social relations which define personal and social identity are shaken and shattered by the powerful global forces of Modernity. James Hunter elaborates on impact of Modernity: “Modernity can be defined both as a mode of social life and moral understanding defined by the autonomous and imperial self, the differentiation of spheres of life-experience into public and private leading to corrosion of social institutions and fragmentation of life; and the pluralization and competition of truth claims which undermine any claims of universal truth and moral.5Philip Sampson, Vinay Samuel, et al., Faith and Modernity (Regnum Lynx, 1994), pp. 16-17.

The occupations of most people in pre-technological society remained much the same for most of their lives. The lack of social mobility ensured that people were identified with the occupational services which they provided in certain local communities. One could be known as the blacksmith of Bethany, the tailor in Tyre, or the carpenter of Nazareth. However, modern mass education has created new opportunities for people to change their occupations in their career life. Modern workers find it easy to travel to gain new employment away from their hometowns. For example, in the past, Angela would have remained as a farmer in her village and a poor aunt to her relatives. But nowadays, she could learn new skills and migrate to the city to work as a skilled worker in a factory or as an executive in a business corporation. If Angela is enterprising and successful in her new career, she may even become accepted as an honorable member of an exclusive social club. In short, Angela acquires differing identities in the course of her upward social mobility. But when she travels back to her village, she is still Aunt Angela, though an aunt with some financial means. The ease of travel to multiple locations and communities requires Angela to switch her identity frequently, depending on which social network she is engaging with.

The conditions of modernity have rendered personal identity fluid with the ever-changing flux of social relations while propelling social life away from the hold of pre-established precepts or practices of rural society and creating new opportunities in work and living in urban society. Anthony Giddens describes how Modernity has the capacity to disembed individuals from their local social relations and reconfigure them across indefinite tracts of time-space. This is facilitated by disembedding mechanisms such as “symbolic tokens” (such as money) that free owners from being chained to immovable properties, and “expert systems” which provide assistance to people solving problems encountered in settling down to a new life. As a result, “personal identity is no longer restricted to local spatial and time markers or local community relations, but may be reembedded and reconfigured across space-time.”6See, Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity (Polity Press, 1991), p. 18 and Consequences of Modernity (Polity Press, 1990) pp. 21-35.

The phenomenon of fluid identity is also intensified by the impact of modern industrial processes which result in fragmentation of consciousness for individuals. Peter and Brigitte Berger in their book, The Homeless Mind have delineated the mental map of workers involved in processes of modern technological rationality and productions which displays the following characteristics: mechanisticity, reproducibility and self-anonymizing participation in a mass production assembly setting. Their analysis of the cognitive style of the worker identifies the following traits: componentiality, interdependence of components and their sequences, the separability of means and ends, a pervasive quality of implicit abstraction, the segregation of work life and private life, and anonymous social relations. The authors suggest that “Individuals become organized in accordance with the requirements of technological reproduction.” Technological production is also based on anonymous social relations. The result is that the “modern self” experiences itself as a componential or fragmented self. This poses the challenge of how one could manage emotional trauma where the logic of production dictates control over free-flowing emotionality given the precarious situation of meaninglessness, disidentification and experiences of anomie.7Peter Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner, The Homeless Mind (Pelican Books, 1973), pp. 32-42.

Marshall Berman draws wider implications of the paradoxes and promises inherent in modern life which is characterized by rapid change, innovation, and a constant state of flux. Berman posits that while modernity offers transformative power and new opportunities, it also brings about alienation and upheaval. His graphic description of the impact of modernity on North Atlantic societies remains pertinent today.

To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world – and, at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are…modernity can be said to unite all mankind. But it is a paradoxical unity, a unity of disunity; it pours us all into a maelstrom of perpetual disintegration and renewal, of struggle and contradiction, of ambiguity and anguish. To be modern is to be part of a universe in which, as Marx said, ‘all that is solid melts into air.8Marshall Berman, All that is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (Simon Schuster, 1982), p. 15.

Not surprisingly, a sense of anomie and collective futility becomes pervasive in modern society: “the futility of a life which does not fix or realize itself in any permanent subject that endures after its labor is past…He [Marx] knew we must start where we are: psychically naked, stripped of all religious, aesthetic, moral haloes and sentimental veils, thrown back on our individual will and energy, forced to exploit each other and ourselves in order to survive; and yet, in spite of all, thrown together by the same forces that pull us apart, dimly aware of all we might be together, ready to stretch ourselves to grasp new human possibilities, to develop identities and mutual bonds that can help us hold together as the fierce modern air blows hot and cold through us all.”9Berman, All that is Solid Melts into Air, 128-129.

Individuals tossed about by the maelstrom of overwhelming change are driven to look within in a desperate attempt to get a grip of his floundering self. The unintended consequence of Modernity is an obsessive focus on one’s inner self. Ironically the self that is isolated from the dynamics of social relations becomes an empty and undefined ‘self’. Philip Rieff identifies the pathologies that accompany the modern quest of the inner self, “This new ideal pits the individual against tradition and authority. It breaks communal ties and is suspicious of institutions. The new center is the self. “By this conviction a new and dynamic acceptance of disorder, in love with life and destructive of it, has been loosed upon the world.” The therapeutic of the unencumbered self represents “a calm and profoundly reasonable revolt of the private man against all doctrinal traditions urging the salvation of self through identification with the purposes of community.”10Philip Rieff, Triumph of the Therapeutic (Harper & Row, 1966), pp. 5, 242-243.

The modern unencumbered individual whose identity is not defined or limited by the fundamental relationships into which he is born is detached. At the same time he is more expansive in being willing to adopt any resource in his desperate bid to recentre his inner self and regain a coherent identity as he implements his DIY self-reconfiguration project in the void.

Related Post

The Vanished Soul and Quest for the Authentic Self in Modern Western Thought

Forthcoming

The Triumph of the Therapeutic

Kam Weng,

Excellent as always. And I find this ontological discussion helpful in my engagement in the social world – whether religious or in context of modernity.

The fragmentation and unencumbered self, a fluid identity of what I should be is all real and manifest itself in debates and views, often exerting oneself as the right and only.

So too in the spiritual, the void is always substituted by another, fetish, activities of fun and excitement, and to an extend, manifested in the church as well. The comforting and therapeutic seems to be the trend these days.

But what is the churches messages to all this? Correct me if I’m wrong, it seems to me churches (and my own church too) have yet to find a message to meet and address these challenges. Or I’m being to pessimistic here.

I look forward to your “Triumph of the Therapeutic” next….