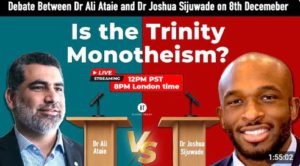

Debate: Is the Trinity Monotheism?

Debate: Is the Trinity Monotheism?

Joshua Sijuwade’s philosophical model of the Trinity is sophisticated and impressive. His analytical model of the Trinity is logically coherent, but as any logician or mathematician knows, one can always construct a consistent philosophical (or mathematical) system based on a chosen set of definitions, assumptions or axioms (so long as it does not claim completeness). More importantly, theoretical models, however sophisticated or coherent, must be grounded in historical reality and divine revelation. In this regard, viewers of the debate need to be convinced that Sijuwade’s splendid system of philosophical trinitarianism is consistent with biblical revelation and the Trinitarian doctrine which was framed in the Nicene Creed (AD 325, 381).

Ali Ataie suggests that the chart or Trinitarian scheme presented by Sijuwade is a form of Sabellianism. He also refers to Origen to suggest that Sijuwade’s monarchical model is not exactly (classical) Trinitarian since his model implies that only the Father has aseity, but not the Son or the Holy Spirit. Even then the Father’s aseity is not intrinsic (which is evidence that Ali does not fully understand the meaning of such a fundamental concept as aseity). Ali even argues that the Father cannot be fundamental since his identity as Father is dependent on another person outside of himself. Sijuwade needs demonstrate how Ali’s misrepresentation and concerns were already addressed by the theological concepts used in the Nicene formulation of the Trinity such as “substance” (ousia), “persons” (hypostasis) and the subsistent relations within the Trinity, eternal generation of the Son, perichoresis, divine persons and missions etc. and show how his philosophical model of the Trinity is consistent with the “grammar” of Nicene doctrine of the Trinity. Since Sijuwade did not ground his abstract Trinitarian model on the history of the Nicene Trinitarian debate and later Christian trinitarian tradition, he was easily (or deliberately) misunderstood to be defending neither the foundational monotheism of the Bible nor the Trinitarian implicate of the incarnational revelation of Christ. Ali shrewdly exploited the lacuna in Sijuwade’s presentation to undermine his argument.

Sijuwade would have been more persuasive if he had demonstrated how his trinitarian model is based on biblical presuppositions. Ironically, Ali refers to the Bible and the early development of the doctrine of the Trinity more than Sijuwade during the debate. Ali gives the impression that his rejection of the Trinity is not based only on logical reasoning but on his expert reading of the Bible. His listeners may be impressed by his references to authoritative texts in biblical scholarship. However, caution towards Ali’s expertise is in order.

First, Ali’s argument of henotheism (in contrast to universal monotheism) of the Old Testament is debatable as it is grounded in the 19C scholarship based on the evolutionary theory of religions.

Second, his suggestion that monotheism is “qualitative” based on the discussion of the “Two Powers” in heaven in Second Temple Judaism (c.f. Alan Segal) and its impact in the development of New Testament monotheism, which according to Ali is “henotheistic polytheism” and not “Unitarian monotheism” nor “Latin trinitarinism”, rests on a misreading of Larry Hurtado’s seminal work, One God, One Lord: Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism. Ali also ignores Hurtado’s conclusive refutation of this “heresy” recorded in Hellenistic Judaism and rabbinic tradition, based on historical and textual evidence.

Third, Ali’s handling of the New Testament lacks grammatical and contextual nuances. For example, his reference to ho theos (“the high God” or the Father) and Jesus (theos, a “low god”) fails to understand the nuances of the use of the definite article in Greek grammar (refer to standard grammar text by A.T. Robertson and Daniel Wallace).

Finally, his argument against the deity of Jesus Christ based on the grounds that Jesus Christ confessed that “the Father is greater than I” and displayed human limitations ignores the historical context where these examples refer to the Son in his incarnate state rather than to his eternal relation with the Father within the Trinity. In short, Ali’s hermeneutics is flawed since it ‘flattens’ the biblical texts to one, horizontal, human dimension rather than situate them in the context of the salvation history of the humiliation and glorification of “Christ who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant… being born in the likeness of men…Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name…and every tongue [should] confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Philippians 2: 6-11).

Ali’s hermeneutical error is common among Muslim apologists who privilege the incarnational or human existence of Jesus Christ in order to argue for the inferiority of the Son. The argument is aimed at undermining the foundation of the doctrine of the Trinity. That is to say, since ontological unity between two beings of unequal natures is impossible, there can be no essential unity (homoousia) between the Son and the Father; there can be no trinitarian-monotheism. Christians are acting without rational justification when they elevate inferior beings like the Son (or the Holy Spirit) to share the same status with the Father. Worse, they are effectively promoting polytheism.

However, the Nicene theologians (4C AD) have already refuted Ali’s argument with the teaching of the eternal generation of the Son by the Father, that is, the Father’s eternal, intimate, and personal causing of the Son without change, division, or imperfection. Eternal generation precludes the idea that the Son is a creature and safeguards the eternal unity and equality of the Son with the Father (or the eternal co-equality of persons within the Trinity). As Glenn Butner explains, “Eternal generation in particular also entails that the Son is not Son due to the incarnation or resurrection but is eternally so and is therefore best known by this title.” It should be noted that only the divine person is generated, not the divine essence. Hence, Butner echoes Francis Turretin who emphasized that the Son does not derive his existence from the Father, which might seem to jeopardize aseity, but his mode of subsisting is determined and derived from the Father.1Glenn Butner, Trinitarian Dogmatics (Baker, 2022), pp. 62, 63.

Sijuwade’ s argument that Biblical Trinitarianism is truly monotheism would have been strengthened considerably if he had drawn resources from the Nicene tradition to expose Ali’s faulty hermeneutics of biblical passages and correct his various misconceptions of early Christian trinitarianism.

Caveat

The above comments are focused on issues arising immediately at the debate between Sijuwade and Ali Ataie, which is to explain why the doctrine of Trinity is not necessarily tritheism. However, in terms of in-house Christian debates on the Trinity, Classical Nicene Trinitarian would need to pose a caveat on Sijuwade’s “Monarchian” Trinity model.

First, Nicene Trinitarianism teaches that the three Persons share equally and eternally the one divine essence. The distinctions between the Persons are based on their relations with one another. In contrast, Sijuwade teaches that the Father is the sole font or source of divine essence. The Son and Spirit are causally dependent on the Father.

Second, for Nicene Trinitarianism, the unity and oneness of will of the persons lies in their shared essence. However, Sijuwade teaches that unity lies in the monarchy of the Father as the cause.

Nicene Trinitarians who uphold the three Persons as being eternally coequal in essence and power have concerns that Sijuwade’s monarchical trinity model which envisages the “ontological causal priority” of the Father” could lead to subordination of the Son and Spirit (Arianism), and some forms of the questionable teaching of Social Triniarianism.

———————–

Reading: Bavinck on the unity of divine essence and distinction of the three persons in God.

For Bavinck, it is inappropriate to prioritize the oneness or the Threeness of God as this would suggest that the divine essence exists in distinction from the three persons. God’s divine essence exists in the divine persons. (Sijuwade’s diagram also seems to suggest the priority of divine essence. It is also understandable if one reads Sijuwade to be prioritizing the Father ontologically).

Bavinck writes,

According to nominalism, “being” – that which is common or universal in any given category – is no more than a “name,” a concept or term. Accordingly, in the doctrine of the Trinity this philosophy leads to tritheism. Excessive realism, on the other hand, associates the word “essence” with some subsistent thing that stands behind or above the persons and so leads to tetratheism or Sabellianism…

Human nature as it exists in different people is never totally and quantitatively the same. For that reason people are not only distinct but also separate. In God all this is different. The divine nature cannot be conceived as an abstract generic concept, nor does it exist as a substance outside of, above, and behind the divine persons. It exists in the divine persons and is totally and quantitatively the same in each person. The persons, though distinct, are not separate. They are the same in essence, one in essence, and the same being. They are not separated by time or space or anything else. They all share in the same divine nature and perfections. It is one and the same divine nature that exists in each person individually and in all of them collectively. Consequently, there is in God but one eternal, omnipotent, and omniscient being, having one mind, one will, and one power. The term “being” or “nature,” accordingly, maintains the truth of the oneness of God, which is so consistently featured in Scripture, implied in monotheism, and defended also by unitarianism. Whatever distinctions may exist in the divine being, they may not and cannot diminish the unity of the divine nature. For in God that unity is not deficient and limited, but perfect and absolute. Among creatures diversity in the nature of the case implies a degree of separation and division. All created beings necessarily exist in space and time and therefore live side by side or sequentially. But the attributes of eternity, omnipresence, omnipotence, goodness, and so on, by their very nature exclude all separation and division. God is absolute unity and simplicity, without composition or division; and that unity itself is not ethical or contractual in nature, as it is among humans, but absolute; nor is it accidental, but it is essential to the divine being.

The glory of the confession of the Trinity consists above all in the fact that that unity, however absolute, does not exclude but includes diversity. God’s being is not an abstract unity or concept, but a fullness of being, an infinite abundance of life, whose diversity, so far from diminishing the unity, unfolds it to its fullest extent. In theology the distinctions within the divine being—which Scripture refers to by the names of Father, Son, and Spirit – are called “persons…God is no abstract, fixed, monadic, solitary substance, but a plenitude of life. It is his nature (οὐσια) to be generative (γεννητικη) and fruitful (καρπογονος).2Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics 2: 300, 308.

The divine nature similarly develops its fullness in three persons, but in God these three persons are not three individuals alongside each other and separated from each other but a threefold self-differentiation within the divine being. This self-differentiation results from the self-unfolding of the divine nature into personality, thus making it tri-personal…3RD 2: 303.

The Trinity itself is as great as each person in it (Augustine, The Trinity, 8.1). Accordingly, the distinction between being and person and between the persons among themselves cannot lie in any substance but only in their mutual relations…The difference did not consist in any substance but only in the relations, but this distinction is grounded in revelation and therefore objective and real. The difference really exists, namely, in the mode of existence. The persons are modes of existence within the being; hence, the persons differ among themselves as one mode of existence differs from another, or – as the illustration has it – as the open palm differs from the closed fist.4RD 2: 304.

The “threeness” derives from, exists in, and serves the “oneness.” The unfolding of the divine being occurs within that being, thus leaving the oneness and simplicity of that being undiminished… Furthermore, although the three persons do not differ in essence, they are distinct subjects, hypostases, or subsistences, which precisely for that reason bring about within the being of God the complete unfolding of that being…The Father is God as Father; the Son is God as Son; the Holy Spirit is God as Holy Spirit. And inasmuch as all three are God, they all partake of one single divine nature.5RD 2: 306.

——–

This brief excerpt does not do justice to the comprehensiveness of the doctrine of the Trinity. It’s relevance to the debate lies in clarifying the unity of substance and distinction of persons in the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Dr Joshua Sijawade is absolutely correct. He’s expressing what’s is precisely the creedal faith of the Apostolic and Nicene Creed. This is what makes the Christian monotheism so unique, without parallel.

However, as Dr Sijawade’s exposition went on, he began to steadily deviate from the Nicene understanding — which is that the substance or essence are not in the all the Three (not a *mathematical* three) Persons equally. He failed to explain that the essence is the Father’s. Hence, the Oneness (not a *mathematical* one) is not *impersonal* but intensely and exclusively *Personal*. As John 17 records, Jesus explicitly refers to the Father as The One True God. God is One precisely because the Father is one. Jesus is true God only because He is *from* the true God the Father and likewise the Holy Spirit. The Cappadocian Revolution occurred precisely because the unity of God is located in the Father Who begets the Son and spirates the Spirit. In other words, the Trinity is located in the Father. The eternal begetting and eternal procession of the Son & Spirit takes places as an intrinsic and inner process within the Father contra Origen, etc. as per the Cappadocian fathers.

What Dr Ali doesn’t grasp and understand is that the Christian concept of person and essence as articulated by the Cappadocian fathers means that the ultimate reality no longer refers to the latter but the former. A person is no longer an instantiation or an aspect of an essence. Otherwise, there would be three Gods. It means that the person is reducible to the essence. Instead, as per the Incarnation, the person is more than the essence. It’s the person that gives existence to the essence in an absolutely unique, particular and unrepeatable manner – the tropos. The essence doesn’t exists apart from the person. In the Trinity, the essence is the Father’s. This means that there’s only one proper divine Individual (individuation) in the Trinity – the Father – and at the same time there’re three Persons. The Father alone is autotheos – God in Himself. The possible distinction between individual and person is what makes possible the divine-human union and communion in the Trinity …

Would like to add some clarifications, re: reading from Bavinck.

Normally we do not speak about about the Trinity being located in the Father. We may say the Godhead is Trinity, or the Trinity is Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Also good to clarify what is involved in the “eternal generation” of the Son. Historically, there are two views which are acceptable to orthodoxy.

1) the Father eternally communicates to the Son the divine essence, so that the Son shares the full essence (deity) of the Father (eternally) – stress “eternal”, or

2) Eternal generation means that the Father begets the distinctive person or mode of existence of the Son (and, by implication, the Holy Spirit), but the Father is not the source of their divine essence. As Calvin put it – the Son is autotheos**.

Calvin wants to avoid a possible misunderstanding of view (1) which some take to mean the Son and Spirit are inferior beings, subordinate to the Father as there are merely recipients of divine essence or attributes from the Father. The Son and Holy Spirit may also not have all the attributes of the Father. I don’t think (view 1) necessarily entails subordination, but Calvin wants to preempt this misunderstanding. This post shows that I favor view (2).

Ongoing debates between these two orthodox possibilities should be welcome.

Regardless, the Oness of God = God unity is a deeply personal unity and it not a substance of impersonal unity. Likewise, the unity of the triune persons is a personal unity = one unity of consciousness and one self-determined will flows through the three persons.

In short, trinitarian theology streses that the Triune God manifests one divine will and inseparable operations of the three persons.

Bavinck’s view is eminently Western and Augustinian.

Nicene Trinitarianism is as articulated by the Cappadocian fathers now represented by Eastern Orthodoxy.

For the East, Triadology cannot be defended on rational/reasonable grounds. One can only demonstrate its inner logic, coherence and consistency.

For example, philosophy doesn’t make the absolute distinction between person and individual.

As per the Nicene confession, there’s only one individual God with equally Three divine Persons.

The only challenge is to demonstrate the inner logic, coherence and consistency.

The contribution of the Cappadocians to the development of the doctrine of Trinity cannot be overstated, especially their innovative use of perichoresis. Yes, there seems to be some differences between Latin Trinity & Eastern Orthodox (Cappadocian) in their initial points, but ultimately we do not have to choose between Augustine & the Cappadocians.

In the end perichoresis prevents distinction within the Trinity from becoming separation & division – whether through the idea of perichoresis as “mutually interpretative motion”, “mutual indwelling,” or “unity of love, consciousness & will.” [Care must be taken not to confuse root word as chorein = to go, make room for & not root word as choreuein = dancing in a chorus which is wrong & misused by contemporary social trinitarianism. That is, Cappadocian trinity is NOT contemporary social trinity (Moltmann). [Editorial note – Craig no longer listed with Moltmann since he is reportedly revising his view on the trinity]

My one requirement is that perichoresis serves to clarify unity in distinction (Cappadocians), but it assumes prior ontological categories that describe the unity and distinction (one being and three hypostases).

I quote Matthew Barrett Simply Trinity – on “The Father is in me and I am in the Father.”—Jesus (John 10:38; cf. 14:10–11, 20)

“But Jesus can only affirm perichoresis if he is homoousios, from the same essence, as the Father. However, he is only homoousios if he is begotten from the Father’s ousia. If not, then perichoresis makes little sense. As Hilary says, “Those properties which are in the Father are the source of those wherewith the Son is endowed.” Hilary elaborates, “The Father is in the Son, for the Son is from Him; the Son is in the Father, because the Father is His sole Origin; the Only-begotten is in the Unbegotten because He is the Only-begotten from the Unbegotten” (The Trinity 3.4). John of Damascus and Thomas Aquinas (who even quotes Hilary) say the same. Unfortunately, social trinitarians have removed perichoresis from its patristic context and redefined it in societal categories.” p. 130.

Yes, Dr Ng. I agree the East and West have irreconcilable fundamental differences on the ordo theologiae – the mode of doing theology.

As a non-scholastic Lutheran, I’ve opted for the ordo theologiae of the East.

The Cappadocian understanding doesn’t preclude the perichoresis. But that the perichoresis isn’t understood as mutual relations, i.e., the reciprocal relationship of the Persons.

This, in turn, presupposes that the Trinity is basically the different relations “of” the Essence. That is, what distinguishes each Person from another is the opposite sides each take in the mutual relation. In other words, “mutual relation is the distinction”.

Whereas for the Cappadocian, the Trinitarian relations are relations of otigin. Only the Father is unbegotten. This isn’t a common “attribute” of God but a specific hypostatic disinction- unique only to the Father. As such, distinction is in the specific hypostatic features.

So, yes, not only is the Son in the Father but the Father is in the Son too. All the while, howevet, the Essence is the Father’s (as per the Nicene Creed). This means that the Essence is in the Father. So that the eternal generation of the Son and the eternal spiration of the Spirit takes place from within the Father.

The Essence is not conceived on is own but always as the Father’s personal or hypostatic feature – Unbegottenness.

That is, the Essence doesn’t have an ontological or metaphysical category on its own other than serving to denote the common God-ness or divinity or deity of the Three Persons.

And also to distinguish the Persons from Nature (Essence, Substance). That is, the Persons are not instantiations of Nature. The Nature is the content of the Person but the Perdon is always more than the Nature.

As inconprehensible as per the East, the Essence is anti-speculative.

The Essence serves to negate and turn philosophy inside out by reorienting the focus on the Persons as the ultimate and, thus, concrete reality. Thus the use of the term “hypostasis” rather than ousia or phusis (or substantia in Latin). “Hypo” as denoting that which stsnds below – the thicker stuff of the dregs of the winepress rather than thinner stuff of the liquid.