Some readers of my earlier posts on Liberal theology have challenged me to explain what I mean when I refer to Liberal theology. It is claimed that the word ŌĆ£LiberalismŌĆØ has been abused to disabuse and slander other believers simply because of some ŌĆśminorŌĆÖ theological differences. Truth be told, liberalism is no minor theological issue. It is a dangerous distortion of biblical Christianity precisely because it uses familiar theological term but invests in these terms meanings that are contrary to what the Bible originally teaches.

Liberalism is the reigning paradigm among biblical scholars and theologians teaching in Western secular universities today. I recommend my readers read John Barton, A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths (Penguin, 2020) to become acquainted with contemporary liberalism.

A cursory reading of BartonŌĆÖs book shows that doubts about the historical reliability of the Bible run through the whole book. Given below is a small sample of BartonŌĆÖs skeptical conclusions:

A cursory reading of BartonŌĆÖs book shows that doubts about the historical reliability of the Bible run through the whole book. Given below is a small sample of BartonŌĆÖs skeptical conclusions:

1. Barton challenges the traditional idea of Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch and endorses the Documentary Hypothesis (J, E, P, D) which regards the Pentateuch as a composite work drawn from multiple sources.

2. The creation accounts of the Book of Genesis are mythological and the Patriarchal narratives of the Pentateuch originated from sagas or folk tales. Much of the narratives ŌĆ£is either fiction or artificially constructed story, even when there is a core of historical reality behind the accounts.ŌĆØ

3.┬Ā The Bible was influenced by the ideas of surrounding Mesopotamian and Canaanite cultures. This undermines the idea of the uniqueness and divine origin of the Old Testament.

4. The predictions of the national disaster of the ancient kingdom of Judah with the destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BC, including IsaiahŌĆÖs prophecy of the return of the exiles are not real prophecy. They are prophecies vaticinium ex eventu or prophecies written after the event. The initial oracles of the prophets were gathered by their disciples which Barton describes as cryptic, chaotic, confused, muddled and obscure. But the oracles were worked over by scribes exiled to Babylon so that the final version of the prophecies retrospectively predict the national disaster as a judgment of IsraelŌĆÖs┬Ā national apostasy from faith.

5. The Gospels are not eyewitness accounts or historical biographies, but are theologically-biased narratives created by people who did not know Jesus personally. Hence, contradictions are found in the Gospels, as evident in the birth narratives and resurrection accounts of Jesus.

6. Quite a number of the New Testament letters are forgeries. Not surprisingly, we find contradictions between portrait of Paul found in the Acts of the Apostles and the Paul in the┬Ā Pauline epistles which prove that both portraits are historically unreliable.

7. Barton suggests that the diverse and often conflicting theological perspectives found in the New Testament reflect the lack of uniformity, if not, conflicting beliefs in early Christian communities.

8. Barton asserts, ŌĆ£The New Testament supports at most a subordinationist Christology, that is, one in which the Son is of a lower status than God the Father.ŌĆØ This contradicts the orthodox doctrine of the divinity of Christ and the Trinity.

The┬Ā pervasive skepticism of Barton is reflective of the view of most liberal scholars today. The sophistication and erudition of liberal scholars is impressive, but the background control beliefs and presuppositions of their methodology of unbelieving historical criticism (in contrast to believing historical criticism) can only lead to doubts about the historical foundations of the Bible. The consequence is rejection of the Bible as an authentic record of revelation from God which serves as the normative basis for the fundamental doctrines of biblical Christianity. As such, liberal scholarship remains as dangerous as ever before.

Evangelical scholars who advocate setting aside doctrinal differences so that the church may present itself as a united household to the world are sincere, but they are sincerely mistaken. It is good always to bear in mind the counsel given by Richard Baxter,ŌĆ£In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, in all things charity.ŌĆØ But unity in Jesus Christ must be a unity of the truth taught in the Bible. In contrast, unity with liberalism is possible only at the expense of compromising the fundamental doctrines taught in the Bible.

Generous-hearted evangelicals who are willing to set aside fundamental doctrines for the sake of unity need to be reminded that doctrine matters as wrong doctrine brings debilitating consequences to the life and mission of the church. Christians need to take heed of the injunction issued by the Apostle Paul, ŌĆ£Follow the pattern of the sound words that you have heard from me, in the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus. By the Holy Spirit who dwells within us, guard the good deposit entrusted to youŌĆØ (2 Tim. 1:13-14).

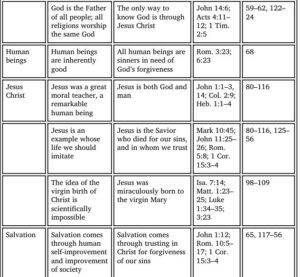

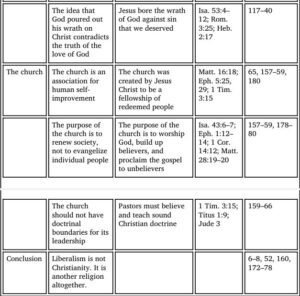

The challenge of liberal scholarship to biblical Christianity is not new. One hundred years ago, J. Gresham Machen pointed out with stark clarity in┬Ā his classic book, Christianity and Liberalism,┬Ā the difference between Christianity as taught in the New Testament and liberalism. MachenŌĆÖs conclusion is that liberalism is not Christianity. It is another religion altogether.

Wayne Grudem gives a chart which helpfully summarizes MachenŌĆÖs arguments.

Source: Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 2e (IVP, 2020), pp. 78-79.

https://www.catholic.com/magazine/print-edition/scott-hahn-on-the-politicized-bible ” HAHN As Robert and Mary Coote readily demonstrate in Power, Politics and the Making of the Bible, historical-critical methods are employed to find political motives behind the narrative text. For instance, when you divide up the Pentateuch into four sources-J, E, D, and P-J, the Jahwist, supposedly was a tenth-century monarchist who supported the Davidic regime down south, in Judah, whereas E, the Elohist, was a representative of the Northern Kingdom, made up of the ten tribes that had revolted against the Davidic empire.

The narrative stories in Genesis that seem to support the Davidic monarchy are ascribed to J, while the stories that would tend to support the revolutionary policies of the northern tribes that formed the Israelite kingdom are ascribed to E.

Of course, the cultic, ritual, and sacrificial ceremonies are identified with the much later source P, since they represent the interests of the priestly editors who, after the Babylonian exile, took Jerusalem and built a theocracy under their own control with a priestly monopoly maintained by the very rituals that their rewritten Bibles now stipulated. (This is nothing but Realpolitik. )

As scholars (such as J. D. Levenson at Harvard) point out, many historical critics simply read political interests into ordinary historical discourse, when in fact their conclusions simply reflect their own political outlook-their own anti-Judaism, especially in the case of German scholars of the 1800s, but also a deeply embedded anti-Catholicism.

YouŌĆÖll find Julius Wellhausen doesnŌĆÖt even make an attempt to hide his animus against Roman Catholicism. He sees Jewish ritual in the Old Testament as an ugly precursor to medieval Catholicism.

Albert Schweitzer made a similar observation about the many lives of Jesus written by New Testament Gospel critics: Staring down the well (of history), what they take for the face of Jesus is nothing but their own reflection at the bottom.

Bismarck promotes historical criticism”