[At the heart of Calvin’s insight is his insistence that social life needs to be regulated by a social apparatus. Religious values are best maintained and transmitted through social institutions]

Calvin upholds both the individual and society. He reminds Christians that they participate in the reign of Christ not as isolated individuals but as a new community in which the members mutually nourish one another’s faith with the variety of gifts they have received:

It is as if one said that the saints are gathered into the society of Christ on the principle that whatever benefits God confers upon them, they should in turn share with one another…it is truly convinced that God is the common Father of all and Christ the common Head, and being united in brotherly love, they cannot but share their benefits with one another. (Inst. 4.1.3).

It may be noted that Calvin’s concern remains within the framework of the orders that God has ordained for the human community. Thus, in contrast to much of contemporary Protestant individualism, Calvin constantly reminds his readers that reconciliation with God is inconceivable apart from the closest bonds of fellowship with the other members of Christ’s body: “For if we are split into different bodies, we also break away from Him. To glory in His name in the midst of disagreements and parties is to tear Him in pieces…For He reigns in our midst only when He is the means of binding us together in an inviolable union” (Commentary I Corinthians 1:13).

At the heart of Calvin’s insight is his insistence that social life needs to be regulated by a social apparatus. Religious values are best maintained and transmitted through social institutions. /1/ Calvin goes further to enlist the power of civil government to promote and ensure constructive social conduct:

For spiritual government, indeed, is already initiating in us upon earth certain beginnings of the Heavenly Kingdom, and, in this mortal and fleeting life, affords a certain forecast of an immortal and incorruptible blessedness. Yet civil government has its appointed end, so long as we live among men, to cherish and protect the outward worship of God, to defend sound doctrine of piety and the position of the Church, to adjust our life to the society of men, to form our social behaviour to civil righteousness, to reconcile us with one another, and to promote general peace and tranquility. (Inst. 4.20.2)

Calvin’s conservative position becomes evident when he suggests that the role of government must go beyond maintaining public peace and protecting the private property of citizens. Civil government has also the responsibility of being a channel of God’s paternal care. Calvin argues that as an earthly father oversees the physical and spiritual development of his children, likewise, civil government has a duty to protect and nurture “the true religion (vera religio), which is contained in the law of God” (Inst. 4.20.3, 6; see also 4.20.9). This includes the authority to ban idolatry, blasphemy and slanders against the truth. To be fair, Calvin expects that a proper reflection of God’s paternal care would require the civil authorities to execute righteous judgment and protect the vulnerable from the oppressor and defend the poor and needy. “Defend the poor and fatherless; do justice to the afflicted and needy. Deliver the poor and needy; rid them out of the hand of the wicked” (Psalm 82:3, 4; Inst. 4.20.9). That is to say, imaging God means fulfilling God’s commission to do the work of edification (Inst. 4.20.4).

“To sum up,” says Calvin of all these authorities, “if they remember that they are vicars of God, they should watch with all care, earnestness and diligence, to represent in themselves on behalf of others [hominibus] some image of divine providence, protection, good, benevolence and justice.” Calvin concludes that “there is no kind of government more salutary than one in which liberty is properly exercised with becoming moderation and properly constituted on a durable basis.” (Inst. 20.7, 1543 edition) /2/

Detractors would insist that a close working relationship between civil and church authorities to regulate social life amounts to oppression by an established religion in Calvin’s Geneva. But we should consider whether Calvin’s theology on balance was more positive towards social freedom. /3/ The danger of religious domination should be acknowledged of course, but one should take into consideration the mitigating historical circumstances of Calvin’s Geneva.

First, Genevan citizens were, at least by profession, followers of the same religion. The need to base public laws on Christian morality was not in dispute. As the civil order in Geneva was based on some form of covenant or social contract that entailed election and accountability of officials, the citizens of Geneva were active participants in the political processes in this small city-state. Indeed, the Genevans themselves were more aggressive than Calvin in implementing public regulations to ensure social cohesion and political unity because Geneva was then facing military threats from its hostile neighbors.

Second, Calvin struggled continuously to ensure good governance which would include built-in checks and balances to prevent abuse arising from human sin. As he says, it is “safer and more bearable for a number to exercise government.” This is so because such number will be able to “help one another, teach and admonish one another,” and even “if on asserts himself unfairly, there may be a number of censors and masters to restrain his willfulness.” (Inst. 4.20.8). For Calvin, any form of government could discharge a measure of its divinely-appointed duty. However, he personally preferred an ‘elective’ aristocracy as he was only too aware that monarchs in his time were prone to abuse their powers. Indeed, the state is not necessarily a higher expression of moral ideals and may even be an avenue of collective egoism under the guise of divine legitimation. /4/ For the same reason, Calvin urges that “this spiritual power be completely separated from the right of the sword”. He assumes that the church of the saints should be administered “not by the decision of one man but by a lawful assembly” (Inst. 4.11.5); a fortiori, the civil authority is no less required to share power.

While Calvin enlisted temporal government to enforce discipline he delimited its coercive power and drew a line of demarcation between civil government and church government. Specifically, he refused to compromise and share the church’s power of excommunication with the Genevan Council. In effect, Calvin accepted the establishment of religion only because he insisted on a clear demarcation between civil and church government and because no single group in Geneva could arrogate final authority for itself. Power, authority and influence were distributed among Calvin, the pastors, the elected elders and elected council members. In this regard, the Geneva polity was a precursor of modern institutional pluralism.

The combination of checks and balances is exemplified in the “Consistory” of Geneva with its coordination or complementation between civil and church government in looking after the moral and spiritual welfare of citizens. This is the body of church elders, chosen from among secular officials who are charged to work together with the pastors to “keep watch over every man’s life” and “to admonish amiably those whom they see leading a disorderly life.” It should be stressed that the Calvin saw the Consistory as discharging its duty to provide remedial care. Its job was not to punish but to admonish since it had no power to fine or jail those guilty of spiritual misconduct.

Calvin’s insistence on maintaining balance of power between the church and the Geneva Council grew out of theological convictions rather than pragmatic considerations. Calvin was simply spelling out the social-political consequences of his covenant theology with its vision of institutional pluralism characterized by separation, but interdependence between religious and political institutions. In contrast to the idea of individualism and self-autonomy propounded by the European Enlightenment, the covenant highlights corporate solidarity and mutual obligations incumbent on all members of society. Michael Walzer correctly captures the social character of the covenant: “The covenant, then, represented a social commitment to obey God’s law, based upon a presumed internal receptivity and consent. It was a self-imposed law, but the self-imposition was a social act and subject to social enforcement in God’s name.” /5/

The voluntary nature of the covenant strikes a fine balance between an authoritarian ideology of social collectivism and individualistic libertarianism. Freedom is affirmed, but this freedom must be exercised responsibly within a given order where the choices and actions of individuals result in consequences that mutually affect one another. In this regard, the social order is not seen as inhibiting freedom. It merely establishes the conditions upon which freedom can be directed towards good ends if the covenant order is respected, or towards negative ends if the covenant order is disregarded.

Third, Calvin followed Martin Luther’s teaching of the two-kingdom principle which establishes a closer working relationship between the two kingdoms (Inst. 3.19.15). The spiritual kingdom deals with instruction of the conscience in piety and promotes zeal to do God’s work while the political kingdom educates men with regard to duties of citizenship and social obligations. Both of these kingdoms, the church and the civil order, attempt to regulate human behavior. Civil legislation in different circumstances should be enacted according to local cultural patterns and in the best interests of a particular community. But these social particulars must remain at the level of humanities and may be regarded as matters of indifference (adiaphora).

Calvin’s steadfastly insists that the two social orders of state and church must never be confused for each other since they pertain to two different worlds, over which different kings and different laws apply.

There is a twofold government in man: one aspect is spiritual, whereby the conscience is instructed in piety and in reverencing God; the second is political, whereby man is educated for the duties of humanity and citizenship that must be maintained among men. These are usually called the “spiritual” and the “temporal” jurisdiction (not improper terms) by which is meant that the former sort of government pertains to the life of the soul, while the latter has to do with the concerns of the present life—not only with food and clothing but with laying down laws whereby a man may live his life among other men holily, honorably, and temperately… There are in man, so to speak, two worlds, over which different kings and different laws have authority. (Inst. 3.19.15)

However, Calvin notes that rulers are to take a subordinate place to Christ’s lordship in the church.

Whereas kings, in times now over, were virtually the spirit of social life, now Christ is the spirit, and he reigns per se in the Church, “vivifying” its life. “Today” we by no means have earthly kingdoms that are in the image of Christ. Since the coming of Christ, and the differentiation of the Church from the State, the rulers have decidedly taken a subordinate place. The locus per se of Christ’s lordship is the Church. /6/

Fourth, Calvin was profoundly aware of the gap between social ideals and practice even as he made a distinction between the voluntary, free, conscience-regulated conduct within the church and the forced and coerced behaviour outside the church:

For the church does not have the right of the sword to punish or compel, nor the authority to force; nor imprisonment, nor the other punishments which the magistrates commonly inflict. Then, it is not a question of punishing the sinner against his will, but of the sinner professing his repentance in a voluntary chastisement. The two conceptions are very different. The church does not assume what is proper to the magistrate; nor can the magistrate execute what is carried out by the Church (Inst. 4.11.3).

Calvin also recognized that an element of coercion is indispensable to ensure that the political order is adequately maintained, as long term social change can only come from a voluntary obedience that is the hallmark of Christian life and discipline. Social behaviour can be regulated and bad conduct may be suppressed by civil sanctions, but human nature can only be transformed by the grace offered through the Christian covenant community. That is to say, the state can only achieve superficial outward conformity, but genuine social life presupposes a personal experience of the grace of the gospel.

The gap between Christian imperative and civil legislation should be acknowledged. What is more vital is that this gap be bridged by prudence and a godly spirit. Often, the real issue is not about the lack of knowledge about laws; it is about the inward springs of human actions and this constitutes the primary focus of Calvin’s Genevan ministry. Calvin’s legacy lies not in the city’s legislation which he drafted with excellent legal expertise, but in his theological vision of how the church, as God’s renewed community, may make a more lasting contribution towards social life.

Related Post: John Calvin’s Reformation in Context – Calvin’s Social Theology. Part 1/4

Next Post: Calvin’s Response When Civil Government Turns Bad – Calvin’s Social Theology. Part 3/4 (Preview)

APPENDIX: Calvin Overruled Civil Government in Matters of Church Discipline

[The Libertines] practiced adultery and indulged in sexual promiscuity in the name of Christian freedom. And at the same time they claimed the right to sit at the Lord’s table (Calvin in his Letters, 75).

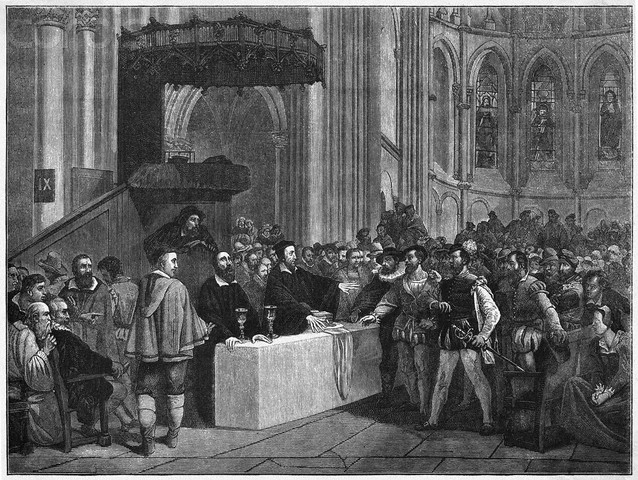

The crisis of the communion came to a head in 1553. A well-to-do Libertine named Berthelier was forbidden by the Consistory of the church to eat the Lord’s Supper, but appealed the decision to the Council of the City, which overturned the ruling. This created a crisis for Calvin who would not think of yielding to the state the rights of excommunication, nor of admitting a Libertine to the Lord’s table.

The issue, as always, was the glory of Christ…The Lord’s day of testing arrived. The Libertines were present to eat the Lord’s Supper. It was a critical moment for the Reformed faith in Geneva.

The sermon had been preached, the prayers had been offered, and Calvin descended from the pulpit to take his place beside the elements at the communion table. The bread and wine were duly consecrated by him, and he was now ready to distribute them to the communicants. Then on a sudden a rush was begun by the troublers in Israel in the direction of the communion table. . . . Calvin flung his arms around the sacramental vessels as if to protect them from sacrilege, while his voice rang through the building:

“These hands you may crush, these arms you may lop off, my life you may take, my blood is yours, you may shed it; but you shall never force me to give holy things to the profaned, and dishonor the table of my God.” “After this,” says, Beza, Calvin’s first biographer, “the sacred ordinance was celebrated with a profound silence, and under solemn awe in all present, as if the Deity Himself had been visible among them” (Calvin in his Letters, 78). [Source: John Piper, The Divine Majesty of the Word. John Calvin: The Man and His Preaching]

ENDNOTES

1. G.R. Dunstan, The Artifice of Ethics (SCM, 1974) and Charles Kammer, Ethics and Liberation: An Introduction (SCM, 1988).

2. Quoted in John Witte, “Moderate Religious Liberty in the Theology of John Calvin,” in the Noel Reynolds & Cole Durham, Religious Liberty in Western Thought (Emory University-Eerdmans, 1996), p. 83.

3. See Alton Templin, “The Individual and Society in the Thought of Calvin,” Calvin Theological Journal 23 (1988), p. 171.

4. For a sobering analysis of the unavoidable conflicts and inevitable inequality and injustice between social groups, see Reinhold Neibuhr, Moral Man and Immoral Society (Scribners, 1932).

5. Michael Walzer, The Revolution of the Saints (Harvard UP, 1965), pp.56-57.

6. Quoted in David Little, Religion, Order and Law (Uni. Chicago, 1969 & 1984), pp. 55-56.