Death, Resurrection and Life Everlasting DRLE Pt.2

Death, Resurrection and Life Everlasting DRLE Pt.2

Death involves disintegration of a person’s vital power, cessation of bodily life, and separation of the body and the soul (nepeš): Gen. 35:18; 1 Kings 19:4). Does the soul continue to exist after the death of the person? The monist theologian’s answer is “no”. Monism argues that according to the Bible, a human being is not divided into separate parts, i.e. body, soul, and spirit, but he exists as a unified or holistic self. Since the soul and the body are just different aspects of a person, existence entails bodily existence. There is no possibility of disembodied existence of the soul after death. The purpose of this post is to show that monism contradicts the Bible which ascribes to the disembodied soul some forms of consciousness in the intermediate state between death and final resurrection.1This post focuses on the biblical teaching on the soul’s disembodied existence in the intermediate state. For a philosophical defence of the tenability of disembodied existence of the soul, see Paul Helm, “A Theory of Disembodied Survival and Re-embodied Existence,” Religious Studies (1978), pp. 15-26; Richard Purtill, “Disembodied Survival,” Sophia 12 (1973), pp. 1-10.

Where are the dead between death and judgment?

In the OT, everyone who dies is described as going to Sheol (שְׁאוֹל šeʾôl). Sheol is feared and abhorred because it deprives every one of one’s life. Sheol can simply mean death (1 Sam. 2:6; Job 7:9; Psa. 88:3; Isa 38:10). Sheol can be a just a reference to a grave. Examples: Ezek. 32:27, where many who were slaughtered were buried with their weapons; Job 17:13-16. Sheol is described as a bed in darkness covered with dust, worm and decay, like a typical Palestinian tomb. Isa. 14:9-20 describes a the fate of a Babylonian king slain in battle and then trampled underfoot. Significantly, the denizens of Sheol, that is the spirits or shades (רְפָאִים֙ rəpāʾîm, rephaim) of Sheol rise up to mock the king for his hubris and humiliating downfall since in Sheol he is reduced to a weak and shadowy existence. The depiction of the spirits in Sheol being ‘alive’ and recognizing the king who just arrived at Sheol, and the contrast between the highest heaven and Sheol as the furthest place below heaven suggest that Sheol is not just a grave; it is also home of the departed in the underworld. It is the context which determines whether Sheol is used literally to describe as a place (as a grave or the underworld) or used figuratively to describe a state of death.

But not everyone is going to the same place after death. When the wicked dies, his soul enters into Sheol, a place of hopelessness and despair (Num. 16:30; Psa. 18:5; Psa. 88:3–5). When the righteous dies his body is buried in a grave, but his soul enters into blessed communion with God (re: discussion below).

Ancient views of the subterranean nether world

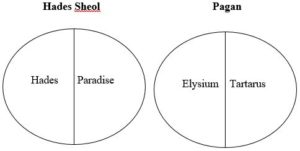

The ancient pagan world – The Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks (Homer and Plato), Romans (Virgil) – believed that all human spirits go to one and same underworld. Over time some Greeks developed the idea of different abodes in the afterlife – Tartarus for the wicked and Elysium for the good. The Old Testament assigns a similar nether world to the dead, but it also suggests that the righteous and unrighteous experience different fates.

The ancient pagan world – The Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks (Homer and Plato), Romans (Virgil) – believed that all human spirits go to one and same underworld. Over time some Greeks developed the idea of different abodes in the afterlife – Tartarus for the wicked and Elysium for the good. The Old Testament assigns a similar nether world to the dead, but it also suggests that the righteous and unrighteous experience different fates.

Due to Greek influence in the intertestamental period, some Jewish traditions (1Enoch; also the Pharisees) assigned the dead to different regions of Sheol, depending on their moral worthiness – punishment for the wicked in Hades, but a pleasant abode for the righteous which is identified as “Abraham’s bosom”(Lk. 16). This tradition became the basis of the medieval Christian teaching of the “harrowing of hell” where reportedly, Christ between his death and resurrection, descended into hell to rescue and bring salvation to the righteous dwelling in paradise. However, other scholars call for caution towards the interpretation which divides Sheol into Hades and paradise since the evidence in the NT remains incomplete (though not necessarily inconsistent).

A closer look at the OT shows that Sheol refers to a place of deep darkness and punishment. However, Sheol is also used in the abstract sense of the power and danger of death as both believers and unbelievers enter the same state of death when they die (1 Sam. 2:6; Job 17:13, 14; Psa. 89:48; Hos. 13:14 note the parallelisn in Psalms and Hosea). Hades is personified in Rev. 6:8. Hades and Paradise should not be placed together in Sheol since “Abraham’s bosom” is both far off (Lk. 16:23) and separated from Hades by a great chasm (Lk. 16:26). In short, “It is only of Sheol as the state of death that we can speak as having two divisions, but then we are speaking figuratively.” [Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (Banner of Truth reprint, 2021,), p. 685] This observation is consistent with the OT’s testimony that the believers who died in the Lord enter into a fuller blessings of salvation (Psa. 16:11; 17:15; 73:24; Prov. 14:32; likewise Enoch and Elijah were spared of experiencing Sheol as they were taken up) in contrast to the fate of the wicked (Prov. 5:5; 15:11; 27:20). The OT believers may be perplexed and troubled by the prospect of death, but they expressed confidence that they will not be separated from God’s care and love in the realm of death.

Regardless, for our present purpose, we note that the prima facie evidence of the Bible shows that: (1) the soul is separated from the body after death, after which, (2) the soul of the unrighteous continues a shady existence in Sheol but (3) the soul of the righteous returns to a provisional blessed existence in the presence of God.

The Bible on the Soul After Death

(1) The soul is separated from the body after death

One fundamental assumption of biblical anthropology is that humans do not have full possession of their breath or ruach. It belongs to God who has the liberty to take back as he pleases. The Scriptures teach that man is a psychosomatic unity, and that “body and soul” (Matt. 10:28) or “body and spirit” (I Cor. 7:34; Jas. 2:26) belong together. But death brings about a temporary separation between body and soul.

Psa. 104:29-30. “When you hide your face, they are dismayed; when you take away their breath, they die and return to their dust. When you send forth your Spirit, they are created, and you renew the face of the ground.”

Job 34:14-15. “If he should set his heart to it and gather to himself his spirit and his breath, all flesh would perish together, and man would return to dust.”

Ecc. 8:8. “No man has power to retain the spirit, or power over the day of death.”

In death, the soul is separated from the body; it becomes disembodied, returns to God and goes where ever God destines it to go.

Matt. 27:50. “And Jesus cried out again with a loud voice and yielded up his spirit.”

Lk. 23:46. Then Jesus, calling out with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” And having said this he breathed his last.

2) The soul of the unrighteous continues a shady existence in Sheol.

The Old Testament warns that the wicked will be punished and sent to Sheol (שְׁאוֹל šeʾôl). The term occurs 65X in the Heb. OT, 61X rendered ᾅδης in LXX. Sometimes it refers to the “grave” where the dead is buried, but more often שְׁאוֹל is a place under the earth where the dead are sent by God against their will. Even the mighty kings on earth are mocked in their weakened post-mortem existence. Isa. 14:9-11 “[All of Sheol] will answer and say to you: ‘You too have become as weak as we! You have become like us!’ Your pomp is brought down to Sheol, the sound of your harps; maggots are laid as a bed beneath you, and worms are your covers.” The NT describes how the souls of the wicked spirits are incarcerated in prison (1 Pet. 3:19) and rebellious angels are committed to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment (2 Pet. 2:4, 9). Hence, Sheol is a prison with gates (Matt 16:18), locked with a key that Christ holds in his hand (Rev 1:18).

Sheol is a place of darkness (Job 10:21-22; Psa. 143:3), silence (Psa. 94:17; 115:17), and forgetfulness (Job 14:21; Psa. 88:10-12). Its inhabitants dwell as “shades” (rephaim), faint shadows of their former selves (Isa. 14:9-10; 26:14). They display some forms of consciousness, albeit in a weakened or shadowy form. Hence, Sheol is a place of despair and hopelessness (Gen. 42:38; Psa. 49:14–15; 88:3–5).

However, despite its terrifying power, Sheol remains under the control of God. It is Yahweh who sends the dead to go down to Sheol. Likewise, he has the power to bring them forth again (1 Sam 2:6; cf. Isa. 26:19). He can deliver his people from the grave (Psa. 16:10; 49:14; 56:13; 86:13). More importantly, God will not abandon his righteous to the corruption of Sheol. In contrast to the false gods and idols only Yahweh could give hope beyond Sheol.

Psa. 16:10. “For you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption.”

Psa. 49:15. “But God will ransom my soul from the power of Sheol, for he will receive me.”

Isa. 26:19. “Your dead shall live; their bodies shall rise. You who dwell in the dust, awake and sing for joy! For your dew is a dew of light, and the earth will give birth to the dead. Isaiah 26:

Job 14:14-17. offers a moment of hope against hope. Job expresses hope that he will see God who will vindicate his righteousness in the final judgment. “If a man dies, shall he live again? All the days of my service I would wait, till my renewal should come. You would call, and I would answer you; you would not keep watch over my sin; my transgression would be sealed up in a bag, and you would cover over my iniquity.”

Job. 19:26-27. For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed,yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

Dan. 12:2-3. The climax of hope beyond death and Sheol in the OT.

“And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.”

What led to Israel’s belief in resurrection? The OT gives two reasons. First, it is the OT affirmation that Yahweh is the living God (Psa. 18:46; Jer. 23:36; Hos. 1:10). With the ever living God, death cannot be the sovereign power in the universe. Hence, Yahweh could deliver the person who had already died (1 Kings 17:17-24; 2 Kings 4:18-37; 13:20-21), and prevent other persons from ever dying (Gen. 5:24; 2 Kings 2:10-11). Death will finally be destroyed (Isa 25:8a). Second, But the living God’s reign of righteousness and justice extends even to Sheol (Job 26:6; Psa. 139:8; Prov. 15:11; Amos 9:2). Vindication will come at the final resurrection where the wicked will be punished and the righteous will be rewarded (Dan. 12:2).

(3) The soul of the righteous enters into a provisional blessed existence in the presence of God.

The Old Testament teaches how the righteous immediately enters into a state of conscious enjoyment of God’s presence when they die. It points to deliverance of several OT personages from dreadful existence inside Sheol.

“Enoch walked with God, and he was not, for God took him” (Gen. 5:24; cf. Heb. 11:5). Elijah did not go down to Sheol, but he “went up by a whirlwind into heaven” (2 Kings 2:11). Significantly, Moses and Elijah appeared, talking with Jesus (Matt. 17:3). David often expresses confidence that he will “dwell in the house of the Lord forever” (Psa. 23:6; cf. Psa. 16:10–11; 17:15; 115:18). Jesus reminded the Sadducees that God says, “I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” The present tense implies that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were living at the moment when Jesus was referring to them. Hence, “He is not God of the dead, but of the living” (Matt. 22:32).

The New Testament confirms the Old Testament teaching of postmortem existence of the soul and that the righteous dead will be in the presence of God.

Matt. 10:28. “Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul (psyché); rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell.” Jesus assures his followers that the soul in them cannot be killed and that it continues to exist after the death of the body.

Acts 7:59. And as they were stoning Stephen, he called out, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.”

Rev. 6:9. “When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls (psychas) of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne.”

Rev. 20:4. “Then I saw thrones, and seated on them were those to whom the authority to judge was committed. Also I saw the souls (psychas) of those who had been beheaded for the testimony of Jesus and for the word of God, and those who had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ for a thousand years.”

The two passages in the Book of Revelation are not referring to living people on earth, but to martyrs who continue to exist despite being put to death, albeit in a form of disembodied existence: (a) The righteous dead are in heaven. (b) They are conscious and resting. (c) They are robed. “Being robed” provides an assurance to the Pauline anxiety about being “unclothed, i.e. disembodied after death. This may also be an allusion of the martyrs being robed in the righteousness of Christ. They are blessed in heaven, c.f. Rev. 14:13. “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.”

Elsewhere in the New Testament, the righteous dead are described as in a state of provisional and incomplete blessedness in the presence of the Lord until they receive the resurrected body.

2 Cor. 5:1–8 “For we know that if the tent that is our earthly home is destroyed, we have a building from God, ma house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens. For in this tent we groan, longing to put on our heavenly dwelling, if indeed by putting it on we may not be found naked. For while we are still in this tent, we groan, being burdened – not that we would be unclothed, but that we would be further clothed, so that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life…We know that while we are at home in the body we are away from the Lord, for we walk by faith, not by sight. Yes, we are of good courage, and we would rather be away from the body and at home with the Lord.”

This provisional or intermediate state after death is preferred to that of life on earth.

Phil. 1:23. “I am hard pressed between the two. My desire is to depart and be with Christ, for that is far better.”

Heb. 12:23. “The spirits of the righteous made perfect”, that is, those who died in Christ are translated into glory and declared righteous. They have been made perfect through Jesus, “the author and perfecter of our faith” (Heb. 12:2). While waiting to receive the resurrected body, they are already perfected in the sense that they are enjoying the presence of God.

Scripture describes the intermediate state of the righteous to be joy in the presence of the Lord. Obviously, the righteous do not received the spiritual, glorified body at death (1 Thess. 4:16, 17 and 1 Cor. 15:52). This will occur in the future, “at the last trumpet”, that is, the resurrection has not yet occurred. There will be a resurrection of both the just and the unjust (Acts 24:15). As Paul assured the Corinthians,

1 Cor. 15:20, 23 –“But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep… so also in Christ shall all be made alive. But each in his own order: Christ the first fruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ.”

1 Cor. 15:52-53 “in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality.”

We end with the following conclusions:

The Bible affirms the conscious existence of both the righteous and the wicked in their disembodied existence after death. However, the biblical evidence is against any suggestion that the souls of both righteous and wicked share the same fate in the intermediate state. The wicked experience conscious suffering. In contrast, the righteous experience conscious joy in the presence of Christ (Phil. 1:23) even as they wait to receive the resurrected body. The final destiny for the Christian is not deliverance from corporeal existence (contra Plato), but attainment of perfected embodied existence in the presence of God.

Related Posts

OT Anthropology. The Constituent Elements of Man

OT Anthropology: Dualistic Holism or Holistic Dualism

————————-

Footnotes