Notes and Reflection on Herman Bavinck, Christian Worldview. Chapter 1. Thinking and Being.

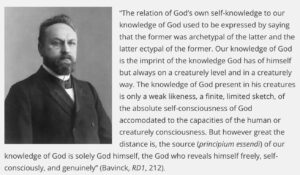

A. Critique of empiricism and rationalism and the Kantian impasse. Empiricism which accepts sense perceptions as the only source of knowledge ends up with subjective representations or mental ideas disconnected from reality. Fluctuating and unstable sensations cannot allow us to see the essence of things.

“For as long as the human being has occupied himself with this problem, he almost always ends up on one side or another, either sacrificing knowledge to being or being to knowledge. Empiricism trusts only sensible perceptions and believes that the processing of elementary perceptions into representations and concepts, into judgments and decisions, removes us further and further from reality and gives us only ideas [denkbeelden] that, though clean and subjectively indispensable, are merely “nominal” [nomina] and so are subjective representations, nothing but “the breath of a voice” [flatus vocis], bearing no sounds, only merely a “concept of the mind” [conceptus mentis]. Conversely, rationalism judges that sensible perceptions provide us with no true knowledge; they bring merely cursory and unstable phenomena into view, while not allowing us to see the essence of the things. Real, essential knowledge thus does not come out of sensible perceptions but comes forth from the thinking of the person’s own mind; through self-reflection we learn the essence of things, the existence of the world.”

However, rationalism which argues that knowledge is attained by reflecting on the ideas of the mind fails to deliver its promise. Contrary to its claim (Descartes), the ideas of the mind are far from being clear and distinct and are basically circular or self-referential.

“No law of cause and effect can release the one who accepts the principle and starting point of idealism from the Circassian Circle [toovercirkel] of his representations: out of one representation he can only deduce another, and he is never able to bridge the chasm between thinking and being by reasoning.” Continue reading “Herman Bavinck: Bridging the Dichotomy between Thinking and Being, and Breaching Kant’s Epistemological Firewall between the Phenomenal and Noumenal. BB001”

Some young Calvinists I know are not sure how to respond to their friends who reject the Calvinist doctrine of God’s foreknowledge and predestination with a self-assured declaration, “No thanks, Calvinist predestination is theologically and logically problematic. I prefer Luis de Molina’s teaching of the “scientia media or middle knowledge as it is more coherent and persuasive.” These young Calvinists become unsettled and feel intimidated by the unfamiliar terminology thrown at them. However, a simple question would dispel the Molinist’s aura of sophistication. “As a Molinist, are you then a Jesuit or an Arminian? Since you are Protestant, I conclude that you are basically rebranding old-time Arminianism by using exotic language, granted that the idea of a divine middle knowledge is at the heart and soul of the Arminian view.”

Some young Calvinists I know are not sure how to respond to their friends who reject the Calvinist doctrine of God’s foreknowledge and predestination with a self-assured declaration, “No thanks, Calvinist predestination is theologically and logically problematic. I prefer Luis de Molina’s teaching of the “scientia media or middle knowledge as it is more coherent and persuasive.” These young Calvinists become unsettled and feel intimidated by the unfamiliar terminology thrown at them. However, a simple question would dispel the Molinist’s aura of sophistication. “As a Molinist, are you then a Jesuit or an Arminian? Since you are Protestant, I conclude that you are basically rebranding old-time Arminianism by using exotic language, granted that the idea of a divine middle knowledge is at the heart and soul of the Arminian view.” What is Biblicism?

What is Biblicism? The book, More Calvinistic Than Calvin? (MCTC) was published in 2023 by a team of local seminary lecturers under the leadership of Bishop Hwa Yung. [The book is available from Canaanland Book Store]. The aim of the book is to refute what it describes as “hardline Calvinism”, and to counter the influence of “hardline Calvinism” among college students in Malaysia.

The book, More Calvinistic Than Calvin? (MCTC) was published in 2023 by a team of local seminary lecturers under the leadership of Bishop Hwa Yung. [The book is available from Canaanland Book Store]. The aim of the book is to refute what it describes as “hardline Calvinism”, and to counter the influence of “hardline Calvinism” among college students in Malaysia. The debate on free will has traditionally focused on how external constraints may prevent us from freely doing what we want to do. In contrast, modern psychology highlights how internal constraints (or drives) such as addictions, phobias and other kinds of compulsive behavior can be even more compelling in determining our actions. Frankfurt introduces several distinctions to our internal constraints or desires in order to shed light on they affect the way we exercise our free will.

The debate on free will has traditionally focused on how external constraints may prevent us from freely doing what we want to do. In contrast, modern psychology highlights how internal constraints (or drives) such as addictions, phobias and other kinds of compulsive behavior can be even more compelling in determining our actions. Frankfurt introduces several distinctions to our internal constraints or desires in order to shed light on they affect the way we exercise our free will.