An interview with Brian Collins, author of Scripture, Hermeneutics, and Theology: Evaluating Theological Interpretation of Scripture. Greenville, SC: Exegesis & Theology, 2012.

You may download a free PDF of the book HERE (a whopping 448MB).

Highlights from the interview. LINK

Modern Historical Critical Methods Renders the Bible Irrelevant

Collins cites Don Carson, “Historical critical methods that are “anti-supernatural” and “determined by post-Enlightenment assumptions about the nature of history” do render the Bible irrelevant. Notably, that is what those methods were designed to do. In short, modern historical criticism has failed in its promise of objective interpretation while also rendering the Bible irrelevant. Theological interpretation of Scripture must integrate exegesis and theology to regain the relevance of Scripture today.

To regain an interpretative method that respects the authority of Scripture and its relevance, Collin begins with A.N.S Lane’s historical survey of the major views on Scripture and tradition in church history.

1. “The Coincidence View.” Scripture and tradition have the same content. Tradition gives us the authoritative interpretation of Scripture. Held by Irenaeus, Tertullian, etc.

2. “The Supplementary View.” Tradition passes on apostolic practices and teachings not found in Scripture. Held to in the later patristic period and in the medieval period. The coincidence view and supplementary view coexisted in the medieval church, but the supplementary view was affirmed at the Council of Trent.

3. “The Ancillary View.” Tradition is often useful, but it is not authoritative. It stands under Scripture. Held by Calvin, Chemnitz, and other Reformers.

4. “The Unfolding View.” Dogma can develop from what was implicit in church tradition. Held by John Henry Newman.

5. Rejection of Tradition held by certain Anabaptist groups in the USA.

Collins favors the ancillary approach:

The ancillary approach has the benefit of truly valuing tradition while not allowing it to exercise authority over Scripture. The history of doctrine or the history of how a particular passage has been interpreted are immensely helpful to alert interpreters to some of their own unexamined presuppositions, to alert them to the variety of exegetical options, or to protect them from recurring heresies that have already been addressed in the past.

Sometimes interpreters implicitly (and maybe even explicitly) take the view that Scripture must be interpreted as meaning x because of certain ANE [Ancient Near East] or Second Temple background or because of certain scientific findings. An ancillary approach welcomes insights from comparative studies or science, but it doesn’t allow them to stand as authorities over Scripture.

[Likewise], tradition (i.e., history of interpretation and history of theology) is hermeneutically useful but not authoritative. While the reader has a place in the interpretive process (e.g., an unbelieving reader will not rightly understand Scripture), the main task of the interpreter is to understand the meaning of the divine Author in the text of Scripture [ with the use of exegesis and theology in the context of the interpretative community – added by NKW].

Integrating Exegesis with Theology

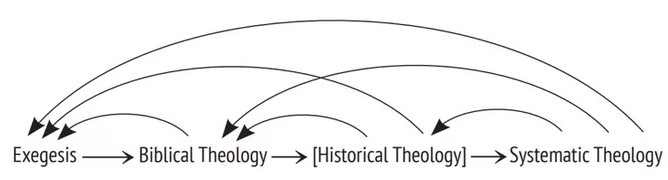

The process of integrating exegesis with theology is best captured by D.A. Carson’s approach that is summarized diagrammatically accordingly:

Collin concludes,

I think the control line at the bottom is very important. Biblical theology needs to be based on exegesis, and systematic theology needs to be based on exegesis and an exegetically grounded biblical theology in light of sound historical theology.

But the arrows that arch back are important as well. When I exegete a text, I should not try to come to it as if I know nothing about the rest of the Bible or the history of Christian interpretation or of systematic theology. Instead, I want all of that to bear on my exegesis of the text. Now, my exegesis may challenge an ST conception. But if it does so, it means I should check that ST conclusion along the control line to see whether or not it is well founded. On the other hand, properly founded ST should govern and delimit my exegesis