For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another (Job 19:25-27).

We secretly relish in schadenfreude when misfortune strikes a wicked man, but we can only be bewildered by the disproportionate suffering that afflicts a righteous and blameless man, like Job. To be sure, we are given a glimpse of divine mystery when the prologue of the book of Job explains that Job’s sufferings are due to a wager between God and Satan. Satan sneers at God and insinuates that his kingdom is based on expediency since Job’s loyalty to God is gained through the blessings of God. God allows Satan to hurt Job, confident that the outcome will conclusively prove Satan wrong.

The extremity of affliction and inexplicable loss suffered by Job drove him to the edge of human endurance even as he hangs on to his faith by the skin of his teeth. Job reels with confusion because according to his inherited theology, God rewards the righteous and punishes the sinner. His immense suffering would thus suggest that he is the chief of sinners, but he knows that he is not. He is forced to choose between the inner conviction of his heart and his inherited theology. With his faith shaken and unresolved, Job finds himself adrift and lost in the turbulent sea with no chart or compass to guide him.

I. JOB’S INCONCLUSIVE DEBATE WITH HIS LEARNED FRIENDS

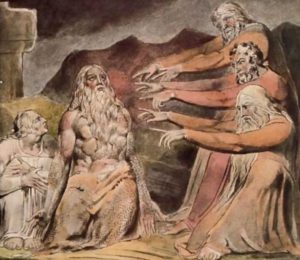

He turns to his friends for sympathy and advice, but instead of giving counsel and comfort they aggravate his grief by suggesting that his suffering is due to unconfessed sin. They are more interested in defending their theological positions than in empathizing with Job in his desperate plight. Eliphaz argues from religious experience, Bildad argues from tradition and Zophar argues from pragmatic common sense.

1) Eliphaz’s Argument from Religious Experience

Eliphaz appeals to his religious experience to support his argument (Job 4:12-17). He shares a private vision of God’s holiness which fills him with dread. “Now a word was brought to me stealthily; my ear received the whisper of it. Amid thoughts from visions of the night, when deep sleep falls on men, dread came upon me, and trembling, which made all my bones shake. A spirit glided past my face; the hair of my flesh stood up. It stood still, but I could not discern its appearance. A form was before my eyes; there was silence, then I heard a voice: ‘Can mortal man be in the right before God? Can a man be pure before his Maker?” (Job 4:12-17).

Eliphaz’s dream leaves him with the profound realization that humanity is insignificant in God’s sight. They may perish forever and nobody cares. Angels are insignificant in God’s sight, much less sinful man (Job 4:17-21). Sinful man will not understand the full mystery of suffering, but the undeniable fact is that God punishes sin (Job 5:6-7). Job’s problem is his refusal to acknowledge his limited understanding of God’s providence and to accept his suffering. Instead he arrogantly demands an answer from God. Eliphaz gives Job a doze of condescending advice, “Remember: who that was innocent ever perished? Or where were the upright cut off?” (Job 4:7) The gist of Eliphaz’s advice is that Job should submit to God’s discipline. “Agree with God, and be at peace; thereby good will come to you. Receive instruction from his mouth, and lay up his words in your heart. If you return to the Almighty you will be built up” (Job 22:21-23). Eliphaz couches his advice as coming from a spiritually experienced and authoritative teacher even as he heaps unfounded accusations rather than kindness on his suffering friend. In reality, he seeks to shame Job into conforming to the pattern of his religious experience. Job retorts that given the intensity of his suffering, he will be dead long before his friend’s hope can be fulfilled (Job 6: 11-14).

Eliphaz reminds us that faith without personal experience can become desiccated; but it is dangerous to turn one’s personal religious experience into a touchstone of religious truth. Eliphaz’s application of his rigid experiential yardstick condemns Job without evidence (Job 6:28-29). Profound truth misapplied causes great hurt. Job rightly rejects Eliphaz’s counsel and instead follows the prompting of his anguished heart to bring his case before God.

2) Bildad’s Argument From Tradition

Bildad rises to defend God’s justice by appealing to the authority of tradition. He rebukes Job for his refusal to confess his sin asking sternly, “Does God pervert justice? Or does the Almighty pervert the right? If your children have sinned against him, he has delivered them into the hand of their transgression. If you will seek God and plead with the Almighty for mercy, if you are pure and upright, surely then he will rouse himself for you and restore your rightful habitation” (Job 8:3-6).

Bildad is not surprised by Job’s suffering. What can sinful man expect? “How then can man be in the right before God? How can he who is born of woman be pure? Behold, even the moon is not bright, and the stars are not pure in his eyes; how much less man, who is a maggot, and the son of man, who is a worm!” (Job 25:4-6). He repeats the standard wisdom that sin reaps punishment while righteousness reaps prosperity. He applies the logic of conventional wisdom to silence Job, “Can papyrus grow where there is no marsh? Can reeds flourish where there is no water?” (Job 8:11). Since there is no smoke without fire, Job had better accept his just deserts. Bildad urges Job to repent as God will honor his word to restore the repentant sinner. “Behold, God will not reject a blameless man, nor take the hand of evildoers. He will yet fill your mouth with laughter, and your lips with shouting” (Job 8:20-21).

We can count on Bildad to be a faithful but superficial defender of inherited theology. He expects life to conform to the pattern described by his tradition. “For inquire, please, of bygone ages, and consider what the fathers have searched out. For we are but of yesterday and know nothing, for our days on earth are a shadow. Will they not teach you and tell you and utter words out of their understanding?” (Job 8:8-10). For Bildad, tradition has identified the direct cause-effect relationship sin and punishment. Job will remain mired in his sin unless he heeds the wisdom of tradition. He rubs salt into Job’s wounds by alluding to the calamities that have fallen upon him: the fire that destroyed his property, the death of his sons and the loss of reputation which led him to be cast out of town to end up sitting on an ash heap (Job 18:14–19, cf. Job 2:7-8). Bildad is relentless in prosecuting his case against Job. He provokes a sarcastic rebuttal from Job who reminds him that cold logical arguments served without love will fail to help men who are beset by moral weakness and sin, “How you have helped him who has no power! How you have saved the arm that has no strength! How you have counseled him who has no wisdom, and plentifully declared sound knowledge!” (Job 26:2-3).

Job concedes that he is not sinless and that even the righteous man cannot stand before the holy God (Job 9:3). But he contends that his suffering seems disproportionately severe. This causes him to voice shocking complaints against God (Job 9:16-20, 29-35). He struggles to keep his faith in God (Job 10:2, 8-11). All he wants is to have a chance to lay his case before God so that he can prove that he is not guilty of the kind of sin that would make him deserve the punishment that he is enduring.

3) Zophar’s Argument from Pragmatic Common Sense

Zophar is the typical man of common sense who manages his life with conventional wisdom. He may be a man of piety, but he is not unduly concerned about the mysteries of God. All that is needed is the simple Gospel. He is furious that Job dares to question the justice of God. A sharp rebuke is in order:

“Can you find out the deep things of God? Can you find out the limit of the Almighty? It is higher than heaven – what can you do? Deeper than Sheol – what can you know?” For Zophar, Job’s “Why?” is his greatest sin, the supreme proof that he has not even begun to walk in the paths of Wisdom: “An empty man will get understanding, when a wild ass’s colt is born a man” (Job 11:7-12).

The recalcitrance of Job betrays sins harboured secretly in his heart. Zophar clearly numbers Job among the wicked who will perish after prospering a short while (Job 15:29-35; 20:4-11), a judgment that must have hurt Job deeply. But Zophar assures Job that all he has to do is to set his heart aright and forsake his sin, and his life will be restored to normal. “If you prepare your heart, you will stretch out your hands toward him. If iniquity is in your hand, put it far away, and let not injustice dwell in your tents. Surely then you will lift up your face without blemish; you will be secure and will not fear…And you will feel secure, because there is hope; you will look around and take your rest in security” (Job 11:13-15, 18). Zophar’s assurance may be patronizing, but presumably they are enough to overcome Job’s recalcitrance and coax him to admit his sins.

We frequently come across friends like Zophar in churches where pragmatism reigns supreme. We are constantly reminded by them to make sure that we do not become too intellectual or abstract in our faith. They may be sincere with their advice but their understanding of God is distorted when they insist that revelation must conform to their limited human judgment. We also cannot help but feel judged by their simplistic answers that have no room for human struggles in the midst of the adversities of life.

How is Job to respond to his three friends’ counsel? His friends continue to view the world through the lens of their respective theories based on experience, tradition and common sense. Their theories may be superficially correct, but Job grasps the deeper meaning of God and his revelation. His bitter experience has opened his eyes to the prevalence of injustice around him even as he vaguely grasps the fact that no human intellect can comprehend fully the almighty God. Still, the reality of his disproportionate suffering must trump his friends’ abstract theories. His wounded soul will experience peace when God eventually answers him. Meanwhile, he feels shut in from every side by overwhelming suffering.

The problem for Job’s friends is that they are pretending to be defending the justice of God when in reality they are only parading their human wisdom with their nicely packaged views of God’s providence. In the end, they become miserable comforters and windbags of sophistries. Their maxims are but proverbs of ashes and their learned discourses futile attempts to justify the ways of God (Job 13: 4-12). Job’s friends are “worthless physicians” when they fail to recognize that Job’s suffering is not only physical, but spiritual. Job’s perplexities intensify because he receives no answer despite his genuine effort to bring his complaint to God. “Behold, I cry out, ‘Violence!’ but I am not answered; I call for help, but there is no justice. He has walled up my way, so that I cannot pass, and he has set darkness upon my paths. He has stripped from me my glory and taken the crown from my head. He breaks me down on every side, and I am gone, and my hope has he pulled up like a tree” (Job 19: 7-10).

Job’s friends repeatedly accuse him of grievous sin. In defending his innocence, Job declares that he has never rejected any legitimate claim put forward by his slaves. He denies being guilty of the sin of idolatry and the worship of money and nature (Job 31:13, 26-40). He considers himself as one who is forgiving and hospitable (Job 31:31-32). He longs to be ushered before the judgment seat and argue his case before God, confident that God will vindicate him in the end (Job 13:13-18). Job’s audacious claims stun his friends into silence. His agony has become so intense that only the voice of God himself can bring relief.

II. GOD ANSWERS JOB OUT OF THE WHIRLWIND

“Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind and said: “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge? Dress for action like a man; I will question you, and you make it known to me” (Job 38:1-3).

At last, God deigns to answer Job’s demand for a hearing, but he answers on his own terms. He does not specifically address the issues raised in the debate. He has no need to defend himself. Neither does he care to give a clear answer to Job’s desperate question, Why? The encounter shows that God is the prosecutor while Job is the defendant. Initial impressions may suggest that God intends to intimidate Job with an overwhelming display of power manifested through the marvels of creation. In reality, God is seeking to temper the bitter refrains of Job’s lament by directing him to contemplate on his gracious providence and good governance of the world.

In his first speech, God invites Job to consider how the stars and constellations are mysteriously structured and maintained by his power (Job 38:4-29:30). It is God who has established the earth on secure foundations, restrains the wild seas and controls the weather. It is clear that God’s sovereignty extends from the microscopic world to the vast cosmos. As he judiciously manages the well-being of all creatures on earth (Job 38:39–39:30), likewise he also exercises care and compassion for human beings. The grand panorama of the marvels of God’s creation helps Job to realize that his puny mind cannot fully fathom God’s wise providence and that his complaint about the lack of justice in God’s temporal judgment is based on flimsy evidence and faulty inferences. Job confesses that he has been both ignorant and hasty in complaining about God’s providence, “Behold, I am of small account; what shall I answer you? I lay my hand on my mouth. I have spoken once, and I will not answer; twice, but I will proceed no further” (Job 40:3-5).

The manifestation of God’s glory and power overwhelms Job, but it also brings him peace. While God’s speech appears to be focusing on the glory of creation, in reality it is addressing a deeper and unexpressed fear within Job, that is, perhaps his unmerited suffering is evidence of the terrifying truth that God is not all-sovereign. God reminds Job that he is misguided when he judges God’s providence based on immediate circumstances, but an awareness of this limited judgment should persuade Job to continue to trust in the sovereign and good God. Hence, while God’s first speech focuses on his gracious providence, the second speech focuses on how God’s justice is built into the fabric of his creation. It is significant that God proceeds from posing unanswerable questions of cosmic mysteries to directing Job’s attention to the mundane matters of this world since man is tempted to think that he can manage these mundane matters with his own resources. God is alerting Job that his pursuit of justice can lead him dangerously down the path of pride and self-righteousness. In seeking to prove his innocence he not only questions the justice of God but also implies that he is able to manage the world better. In effect, Job presumes that he is in a position to bring a charge against God.

Well, God responds with a series of unanswerable challenges to Job. Can Job crush the wicked? (Job 40:8-14). Can Job understand why God created formidable and ferocious monsters like Behemoth (the hippopotamus?) and Leviathan (the crocodile?) (Job 40:15-24; 41: 1-34)? These rhetorical questions put Job in his place when he realizes the futility of trying to confine God within the limits of human rationality. These monsters may appear anomalous to God’s magnificent creation. That they serve a purpose of God unknown to man is evidence of the abundance of God’s grace. Since Job can neither comprehend nor control these creatures, he is in no position to do better than God. Job’s misgivings about God’s moral rule of the world is nothing more than an expression of futility and negativity since he does not have the wisdom and power to do better than God (Job 40:11-41:34). There is no conflict between God’s power and justice as they work together to accomplish his good purposes in the world. Not only is God merciful but his power – which superficially appears to Job and his friends to be unpredictable – is the very guarantee that God is able to achieve whatever he purposes. It is wiser for Job to trust and worship God rather than to try to judge him.

Job’s suffering is no longer unbearable when seen in the light of God’s power, the beauty and harmony of his creation, and the justice of his ways. Job humbles himself before God, relinquishes his protest of innocence and retracts his complaint about God’s just governance of the world. He no longer insists that he be vindicated by God. In humility and trust he acknowledges God’s glory and expresses gratitude to God. God affirms that Job has spoken rightly in his debate with his friends (Job 42:7) but reminds him that he has also spoken foolishly as he contemplates bringing his dispute to God. However, God does not charge Job for further transgressions. Job spoke wrongly because he suffered; he was not suffering because he had sinned. Job now realizes that it is more important to rest his sense of dignity and well-being in his relationship with God and not in his own moral achievement. Job repents in dust and ashes (Job 42:6). He may have lost everything, but he finds peace in surrendering his whole self to God, including his just grievances. God restores his favour towards Job and blesses him.

Related Posts

God Has Answered our Coronavirus Lament. Contra. N.T. Wright

Finding God’s Peace in Times of Afflictive Providence (Covid-19 Crisis)

Trusting God in Times of (Covid) Crisis

Thanks, Dr Ng Kam Weng, for such an inspiring and encouraging post. I pray 🙏 that we too will “find peace in surrendering our whole selves to God, including our just grievances” especially in this catastrophic crisis. Wonderful message for such a time as this!👍👏