(1225-1274). Painting attributed to Botticelli, 1481-82.

Video Link – Thomas Aquinas, Soul’s Powers (Faculties), Cognition & Proof of God’s Existence

Contents of Video

Aquinas’ hylomorphism

– Soul and body are distinguishable realities, ‘incomplete substances’; but together they form one substance, the human being.

– The Soul as a Subsisting Form Configuring Matter.

– Soul survives death (contra Aristotle).

– Powers (faculties) of the human soul.

Aquinas on Cognition-Knowledge

– Common sense, phantasia, agent intellect, possible intellect.

– Sensible species, phantasms

– Active intellect & intelligible species, inner word or concept, possible intellect

– Four different stages – the reception of sensible species; their processing into phantasms; the abstraction of intelligible species; and their processing into intellected intentions.

Arguments for Existence of God

– The First Way: God, the Prime Mover

– The Second Way: God, the First Cause

– The Third Way: God, the Necessary Being

– The Fourth Way: God, the Absolute Being

– The Fifth Way: God, the Grand Designer

You can watch the video at

Thomas Aquinas, Soul’s Powers (Faculties), Cognition & Proofs God’s Existence

Forthcoming Uploads – New series of videos on Biblical-Nicene Trinitarianism vs Early Heresies.

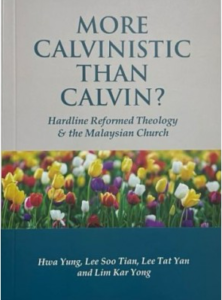

The book, More Calvinistic Than Calvin? (MCTC) was published in 2023 by a team of local seminary lecturers under the leadership of Bishop Hwa Yung. [The book is available from Canaanland Book Store]. The aim of the book is to refute what it describes as “hardline Calvinism”, and to counter the influence of “hardline Calvinism” among college students in Malaysia.

The book, More Calvinistic Than Calvin? (MCTC) was published in 2023 by a team of local seminary lecturers under the leadership of Bishop Hwa Yung. [The book is available from Canaanland Book Store]. The aim of the book is to refute what it describes as “hardline Calvinism”, and to counter the influence of “hardline Calvinism” among college students in Malaysia.

Citizens of two cities

Citizens of two cities